MEASURES OVERALL 6 7/84 7/8 X 4 3/4 INCHES. Abe, who had worked as a police officer and theater manager, died Friday at Castle Memorial Hospital. After being honorably discharged from the United States Army for his service during World War I, Abe became a successful businessman and community leader, owning the Yamato Za, a prominent movie theater in Hilo. During World War II, authorities arrested Abe after a Japanese flag was found in the theater. As a result of his incarceration during the war, Abe was forced to resign as a senator. Abe’s experience reflected the challenges and suspicions facing the Japanese community in Hawai’i during World War II and the large-scale purge of early Japanese candidates and politicians that subsequently occurred. 1 Abe’s Early Career. 2 Abe’s Political Career. 3 Abe’s Internment. 4 Abe’s Postwar Life. 5 For More Information. Abe’s Early Career. Sanji Abe was born in Kailua-Kona on the island of Hawai’i on May 10, 1895, just ten years after the arrival of the first kanyaku imin, Japanese contract laborers. His family, who had arrived from Fukuoka Prefecture in 1893, moved to Hilo when he was about twelve years old. Later, he began working at the Hilo Police Department. Along with other Japanese, Abe was drafted into the United States Army in World War I. At the time, not many Nisei met the age requirements for military service and of the 800 Japanese drafted, more than half were Issei. [2] Abe continued to work at the police department during the war and started to venture into the growing theater business at this time. As movies became an increasingly popular source of entertainment, the Yamato Za and its nearby restaurants grew in popularity. The Mamo Theater, Shindo, Ginza Café, Hinode Café, Yamato Tei Restaurant, and Hama no Ya Restaurant all made Mamo Street a popular gathering place for Hilo’s Japanese residents. In addition to being a fixture in the entertainment business, Abe was also actively involved in the community as the father of six children. After his honorable discharge from the army, he joined the American Legion where he played an active role in the organization’s “Americanization” movement as a charter member and then resident of the Hilo Forum of American Citizens of Japanese Ancestry, popularly known as the Nisei Club. [3] Abe also served as an adviser to the Big Island Japanese Baseball League and even took a Japanese baseball team to the mainland in 1921. Abe was also the vice chair of the Big Island Sumo Association and celebrated his 20th anniversary with the Hilo Police Department by building a monument for deceased immigrants at Hilo’s’Alae Cemetery as well as other cemeteries. As Abe’s prominence began to grow in the community, so did suggestions that he run for political office. Abe’s Political Career. Abe’s political ambitions coincided with the growing presence of Japanese in Hawaiian politics. The first person of Japanese ancestry to run for political office was Ryuichi Hamada of Kaua’i, who ran for the Territorial House of Representatives in 1922, but lost. That year, there were only 1,035 registered voters in the Japanese community and Japanese candidates were uncommon. [4] Despite this early failure, more Japanese candidates followed in 1926 and 1928. In 1930, Masayoshi “Andy” Yamashiro, a Democrat, and Tasaku Oka, a Republican, were elected to the Territorial House of Representatives, becoming the first Japanese elected to that body. In time, more Japanese Americans were elected. In November 1940, Sanji Abe, who by then had risen to the rank of assistant chief in the Hilo Police Department, decided to resign his position to run for the Territorial Senate despite the deterioration of relations between America and Japan by early 1940. In response to growing anti-Japanese sentiment, Japanese American candidates began emphasizing their loyalty to the United States in their campaign speeches while also opposing those who attacked them for retaining their dual citizenship. Abe himself was a dual citizen as Nisei born prior to 1924 were also accorded Japanese citizenship. [5] Abe’s supporters, in turn, accused his attackers of using race to discredit his campaign. [6] During this furor, Abe’s Japanese citizenship was finally removed three days before the election, and Abe was victorious in the senate race, garnering 7,428 votes and making him the first territorial senator of Japanese ancestry. In addition to his political responsibilities, Abe continued to operate the Yamato Za and expanded his business to Honolulu, becoming the president of Kokusai Kogyo. In May 1941, he opened the 1,200-seat Kokusai Theater, showing movies from Japan. However, Abe’s business interests would be abruptly halted with the outbreak of war following the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. In August 1942, Abe was arrested after a Japanese flag was found at his Yamato Za Theater in Hilo. Possibly it was left at the theater by some show troupe appearing there long before the war started, although under my instructions employees of the theater searched the premises several times for just that very thing. [8] Under martial law, the military had been ordered to confiscate all enemy flags, and it was against the law to have a flag in one’s possession. Since the law banning anyone from possessing an enemy flag was to go into effect on August 20, the case against Abe was dismissed on August 18. Despite the dismissal of the misdemeanor charge, a warrant for Abe’s arrest was issued on September 1. The following day, authorities arrested Abe and held him at Sand Island for two months. During his incarceration, Abe was brought before the Board of Officers and Civilians where Lt. In response, Abe introduced into evidence sixteen exhibits consisting of newspaper articles and legislative enactments that he sponsored showing he was pro-American and called a number of witnesses to attest to his loyalty. Although the board found that Abe’s “activities have been both pro-American and pro-Japanese, the later not shown to be subversive, though in some instances, highly suspicious, ” it nonetheless recommended that he be interned for the duration of the war. [9] Abe was forced to resign from his senate seat in February 1943 and a month later was transferred to the Honouliuli internment camp, where he remained for the next seventeen months. Throughout the war, other Japanese American politicians withdrew their candidacies or resigned fearing a similar fate as a result of the anti-Japanese sentiment in the Islands. Thus, between 1943 and 1945 with only one exception, there were no individuals of Japanese ancestry in elected office in the territory despite Japanese constituting nearly twenty-nine percent of the total voter pool. [10] Only a few years earlier in 1941, there had been six representatives and one senator of Japanese ancestry in the Territorial Legislature, along with six Japanese on the county boards of supervisors. Many Japanese candidates who had previously been politically active elected not to run for public office during the war due to the politically volatile situation. In addition, Japanese voters hesitated supporting Japanese candidates for fear that the Japanese community would be seen as trying to take over the government. The Japanese community did not want to exacerbate already strained race relations in Hawai’i as the war provided the opportunity for other ethnicities to express long standing racial fears and hostilities toward the Japanese. Finally, with Hawai’i about to be declared a noncombat zone, the Military Governors Reviewing Board paroled Abe to Wai’alae Ranch on March 22, 1944. As a condition of parole, Abe signed a statement discharging the government and any individuals of any liability as a result of his detention. Abe was finally released on February 16, 1945. Abe’s Postwar Life. In 1960, the Yamato Za was destroyed in the tsunami that hit Hilo. Battling diabetes, Abe decided to move to O’ahu where he lived out his remaining years. In 1968, blind and 73 years old, he said in an interview with the Honolulu Advertiser, I can’t kick too much about [internment]. During a war period, you have to expect anything. And of course times have changed. [12] Sanji Abe died in Kane’ohe on November 26, 1982, at the age of 87. Although the death of Abe was noted briefly in the newspapers, neither the injustices that he suffered nor the purge of loyal American office holders of Japanese ancestry that had occurred during the war were publicly remembered. While the postwar rise of Democratic Party spearheaded by Japanese Americans such as George Ariyoshi, Daniel Inouye, and Spark Masayuki Matsunaga has been well-documented, little attention has been paid to their Republican forerunners like Abe who became causalities of wartime anti-Japanese sentiment. SANJI ABE – PAROLE AND SPONSORSHIP PAPERS. Internees at Honouliuli were permitted to request parole with approved sponsorship assuring close contact, observation of activities and compliance with the terms of release. Sanji Abe was a veteran of World War I and the first Japanese American elected to the Hawai’i Territorial Senate in 1940. He was arrested when a Japanese flag was found in a Hilo theater which he owned. After 16 months of confinement, he wrote a letter to the Military Governor requesting his release, citing a son’s volunteering for the U. He then applied for parole, sponsored by Frank Locey. Locey submitted a sponsor’s report on Abe’s compliance with the terms of his parole. People who study Executive Order 9066 and the Japanese American wartime concentration camp experience often present as contrast the treatment of Japanese Americans in the Territory of Hawai’i. In Hawai’i, which had an even larger ethnic Japanese population than the West Coast, there was no mass removal, and only some 3,000 individuals of Japanese ancestry were ever imprisoned in camps, either on the islands or the mainland. Delos Emmons, the territory’s wartime military governor, well understood that, apart from any moral or constitutional dimensions of the question, any such policy would be doomed to failure on practical grounds. Putting together, in time of wartime scarcity, the resources in food and materials needed either to maintain 150,000 people in close confinement (from which they could be liberated by any Japanese invader) or to transport them to the mainland would be costly if not impossible. Furthermore, the territory’s leaders simply could not afford to incarcerate the bulk of its labor force if they needed to keep up war production, while the politically powerful “Big Five families” who made up the Hawai’i’s ruling class were opposed to losing their plantation workers. Emmons preferred to trust Japanese Americans, and they amply repaid that trust by contributing massively to the war effort in terms of labor in defense industries and enlistment of soldiers. As countless numbers of latter-day scholars and activists have pointed out, the fact that Japanese Americans were left at liberty in Hawai’i, whose territory had been attacked at Pearl Harbor and which remained the most exposed to invasion during the war, lays bare the hollowness of the case for military necessity made by the Army and by those West Coast whites who agitated for the wholesale removal of ethnic Japanese. Put another way, if in Hawai’i, where Japanese Americans constituted some 40 percent of the population, they could be left alone, why could not one percent of the West Coast population be similarly trusted? This argument, to be sure, carries a great deal of truth. However, the argument tends to ignore two essential (and related) points. First of all, averting mass confinement in Hawai’i was a near thing, despite the unrealistic nature of any such project. Plans for mass roundup and confinement of “local Japanese” in Hawai’i removal were drawn up in the spring of 1942 by the joint chiefs of staff, approved by Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox and endorsed by President Franklin D. Emmons (with help from Assistant Secretary of War John McCloy) succeeded in scuttling the plan by a stalling policy, though he did ultimately send 1,000 “potentially dangerous” Japanese Americans and family members – the sacrificial victims of the policy – to camps on the mainland as a gesture of compliance. Emmons deserves enormous credit for his cool-headed balancing of the needs for labor and materials against fears for security. That said, a second and related point is that Japanese Americans, like others in Hawai’i, remained only partly free under wartime military rule. Indeed, beginning in the first moments of the war, their presence gave the Army the pretext to grab absolute power in Hawai’i and cling to it. 7, 1941, as the bombs fell on Pearl Harbor, Lt. Walter Short visited Territorial Gov. Joseph Poindexter and warned of the urgent menace of sabotage by local Nikkei. He insisted that unless the governor granted full powers to the Army he would not be responsible for guaranteeing Hawai’i’s safety, and then threatened to take power unilaterally. Short pressured Poindexter to sign a special martial law proclamation that the governor had never seen. Once Poindexter had signed the proclamation declaring martial law, Short declared himself the military governor, abolished Hawai’i’s government, dismissed the legislature, and suspended the U. When Emmons arrived 10 days later to replace Short, he took on the title and powers of military governor. Military officials, led by Provost Marshal General Thomas Green, imposed a set of general orders to govern the territory. Army rule was marked by harsh and often arbitrary regulations. Newspapers remained heavily censored and criticism of military officials forbidden. The regime imposed stringent labor rules and bans on strikes. Despite promising to restore civilian government, military governors held power for three years, long after any threat of Japanese invasion had passed. While Japanese Americans were not singled out for different treatment in most cases, there were some special restrictions on them. Japanese American farmers in the West Loch area near Pearl Harbor were banished form their homes, though they were permitted to farm the land on their property. Japanese churches and language schools were shuttered. Community leaders such as school principal Shigeo Yoshida, knowing that Japanese Americans were vulnerable, led “speak English” campaigns and war bond drives. Still, it is incontestable that in certain cases the commanders of the military regime used their great power in unjust and arbitrary fashion against Japanese Americans. A case in point is the story of Sanji Abe. Born on May 10, 1895 in Kailua Kona, the son of immigrants from Fukuoka province, he was granted U. Citizenship after Hawai’i was annexed by the United States in 1898. He later moved to Hilo on the Big Island. After serving in World War I, Abe joined the conservative veterans’ group American Legion to assist in the Legion’s “Americanization” program. Meanwhile, he was named president of the “Nisei Club, ” a well-known civic group in Hilo. Hired as a patrolman by the Hilo Police Department, he was later promoted to the position of clerk of the police court, and was subsequently named a deputy sheriff. He also bought a home and various other real estate properties. He also married and had six children. In 1940, running on the Republican ticket, he sought election to the territorial senate. After being repeatedly attacked by a race-baiting white Democratic opponent for his (pro forma) dual citizenship, Abe agreed to formally renounce his Japanese citizenship as a gesture to appease nativists – his expatriation notice arrived a few days before the election. In November of 1940, Abe defeated his opponent, thereby becoming Hawai’i’s first-ever Nisei senator. The next year, following the Pearl Harbor attack, Abe (who was well beyond military age) volunteered as a civil defense worker. Despite (or because of) his position, Abe seems to have been closely watched by the military authorities once war began. According to Hawai’i historian Bob Dye, on July 21, 1942, Abe’s son Stanley accompanied military intelligence agent Samuel H. Snow on an inspection of the Yamatoza theater, of which Sanji Abe was part owner. While looking among the stage properties, Snow announced that he had found a Japanese flag – Stanley Abe, who played in the theater backstage and knew it well, was certain that it had been planted. Abe protested that he had never bought or flown any Japanese flag – and had indeed ordered his theater checked carefully for just such contraband. He also pointed out that the military orders making possession of Japanese flags a crime were not issued until Aug. 8, six days after his arrest. Army officials were thus forced to release him on Aug. Still, even after he publicly burned the offending flag, the following day, Abe remained under suspicion. As if to demonstrate in graphic terms the authoritarian power of the military, in September of 1942 Green had Abe rearrested, this time without charge. Brought before a board made up of a mix of officers and civilians, it was a kangaroo court, with the “evidence” against Abe based on rumor, vague accusations by informants, and a broad dose of racial prejudice; the chief charges against Abe were that he had studied in the prewar era he had studied in a Japanese language school, had traveled to Japan, that he had shown Japanese-language motion pictures in his theater, and that in 1939 he had served on a reception committee for officers of a visiting Japanese naval vessel. Abe produced white witnesses who testified as to his loyalty to the United States. Despite the lack of any evidence presented as to Abe’s purported disloyalty, let alone formal charges against him, the board recommended that he be incarcerated for the duration of the war. As a result, Abe was placed in “custodial detention, ” where he remained for 19 months, first at the Sand Island concentration camp, later at the Honolulu Detention Center. Abe refused to resign despite the pressure. However, in February of 1943, he was barred from taking his seat in the new legislature when it convened, and he reluctantly resigned in order to spare his district from further reprisals. In March of 1944, Abe was granted parole. As a condition of his release, he was required to sign a form waiving any challenge to his detention. During the postwar years, Abe concentrated on his business affairs, and did not speak publicly abut his ordeal. When he was interviewed about his detention in 1968, he insisted that the reasons for his detention were still a mystery to him. When his interviewer asked whether it was the work of his political opponents, he responded, I assume so. Wartime Army rule in the territory represents a unique case in modern U. History where an elected government was overthrown by Army commanders exercising unchecked power. Throughout the war, the Army in Hawai’i used Japanese Americans as scapegoats, and they became proxies in the larger struggle for the constitutional rights of all groups. Despite being a war veteran and a duly elected territorial legislator, Sanji Abe was subjected to arbitrary arrest and imprisonment without charge. His case reminds us that if Japanese Americans in Hawai’i were not confined en masse, they remained subject to official denial of their fundamental rights on racial grounds. Early life and political career. He attended public schools there. After the war, he rose to the rank of deputy sheriff. [3] He was married to Asami Miyose Abe, with whom he had six children. [4] His dual citizenship of the U. And Japan became a hotly discussed issue during his election campaign. [3] His citizenship issues first came to public attention in early October; soon afterwards, Abe announced that he would be renouncing his Japanese citizenship. [5] He received confirmation of his expatriation on November 2. [7] Two days later, he was formally charged with possession of a Japanese flag. [8] However, at the time he was charged, this was not in fact an offence; with martial law in effect, the Army issued an order making this a crime, but that was not until six days after his arrest. [7] As a result, he was released by a military tribunal two weeks later. [9] The flag in question was a prop in a movie theater which Abe owned jointly; he suspected that it had been planted. However, the Army took Abe into “custodial detention” anyway soon after, a fact which they did not publicly announce until September 8. [10] This time, no charge was filed against him. [7] The writ of habeas corpus had been suspended due to martial law. [4] Unable to serve out his term as a state senator, Abe resigned from his elected post on February 4, 1943, stating as his reason that he wished to protect the people of the territory and the legislature from unjust outside attacks. [11] Abe would be held for a total of nineteen months, first at Sand Island, and then at the Honouliuli Internment Camp, where fellow Japanese American legislator Thomas Sakakihara was also detained. [4] He was released on July 12, 1944; in an interview with the Honolulu Star-Bulletin soon after, he stated that “my conscience is clear”. Unlike fellow internee Sakakihara, Abe did not return to politics after the end of World War II. [13] He died on November 26, 1982 at the Castle Memorial Hospital. Authored by Kelli Y. Nakamura, Kapi’olani Community College. Honolulu: The Advertiser Publishing Co. How Bigots’Cleansed’ Legislature in 1942. The Case of Sanji Abe. Honolulu Magazine 37.5 (November 2002): 38-46. The AJA-Their Present and Future. Judgment Without Trial: Japanese American Imprisonment During World War II. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2003. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991. New York Times, Dec. Western Legal History 3.2 (summer/fall 1990): 341-378. Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Hawai’i Council for the Humanities. Bob Dye, “The Case of Sanji Abe, ” Honolulu Magazine, 37.5 (November 2002), 38. Honolulu Advertiser, November 2, 1940, editorial page. “Chairman Spalding’s Protest In Behalf Of Sanji Abe and The Advertiser’s Answer, ” Honolulu Advertiser, November 4, 1940, editorial page. “Sanji Abe’s Expatriation, ” Honolulu Advertiser, November 5, 1940, editorial page. Dye, “The Case of Sanji Abe, ” 42. In the collection of the Resource Center, Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i. Emergency Service Committee, The AJA-Their Present and Future Honolulu: n. “Sanji Abe, 87; first AJA in Isle senate, ” Abe, Sanji. University of Hawai’i at Manoa. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US.

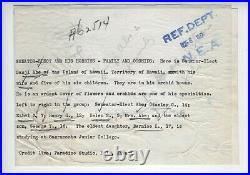

- Type: Photograph

- Antique: No

- Size Type/Largest Dimension: Small (Up to 7\

- Listed By: Dealer or Reseller

- Date of Creation: 1940

- Color: Black & White

- Photo Type: Gelatin Silver

- Original/Reprint: Original Print