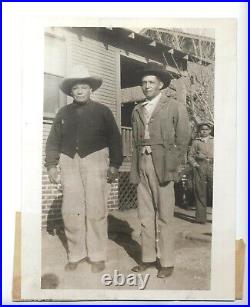

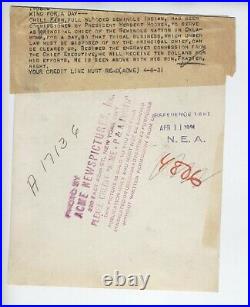

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 6X8 INCH PHOTO FROM 1931 OF CHILI FISH FULL BLOODED INDIAN HAS BEEN COMISSIONED BY PRESIDENT HOOVER TO SERVE AS PRINCIPAL CHIEF OF THE SEMINOLE NATION IN OKLAHOMA, FOR A DAY, THAT TRIBAL BUSINESS, WHICH UNDER LAW MUST BE DISPOSED OF BT THE PRINCIPAL CHIEF, CAN BE CLEARED UP. BESIDES THE ENGRAVED COMMISSION FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE, HE WILL RECEIVE TEN DOLLARS FOR HIS EFFORTS. HE IS SEEN ABOVE WITH HS SON, FRAZIER, RIGHT. Chili Fish, Seminole Indian named by President Hoover as chief of his tribe for a day, has refused the honor, although he maintained that he and other Seminoles were loyal to the United States. The Indian said he would not serve because of the closing of the Seminole Boarding School in Seminole county by the Indian office and also because he did not approve the policies of the commissioner of Indian affairs. Fish, nominal chief of the Oklahoma Seminoles, speaks no English and presented his refusal and reasons in a letter written for him. Fish was named to sign a corrected deed to tribal property following a Government custom to name an official chief each year to transact routine business. Agency officials here said the Indian school Chili Fish referred to had been closed because of a policy of sending Indian children to schools attended by white children to promote closer associations. There were four leading chiefs of the Seminole, a Native American tribe that formed in what was then Spanish Florida in present-day United States. They were leaders between the time the tribe organized in the mid-18th century until Micanopy and many Seminole were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s following the Second Seminole War. Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida. The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida were recognized by the state of Florida in 1957, and gained federal recognition in 1962 as the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida. 1819: Kinache, also Kinhagee ca. 1819, the last chief of the Creek of Miccosukee, Florida, who was defeated in battle in 1818 by US forces commanded by General Andrew Jackson. Later Kinhagee’s people migrated south, maintaining their local village name Miccosukee as the name of the tribe. 2011[5]-2015[6]: Colley Billie, tribal chairman[7], ousted in 2015[6]. Interim tribal chairman[6]. 2015-present: Billy Cypress[3], [6]. Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. 1849-: John Jumper ca. Brown, principal chief[8]. Harjo, principal chief[8]. 2017[9]-Present: Greg P. Chilcoat, principal chief, Tusekia Harjo Band and Deer Clan[10]. The Seminole are a Native American people originally from Florida. Today, they principally live in Oklahoma with a minority in Florida, and comprise three federally recognized tribes: the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma, the Seminole Tribe of Florida, and Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, as well as independent groups. The Seminole nation emerged in a process of ethnogenesis from various Native American groups who settled in Florida in the 18th century, most significantly northern Muscogee (Creeks) from what is now Georgia and Alabama. [1] The word “Seminole” is derived from the Muscogee word simanó-li, which may itself be derived from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “runaway” or “wild one”. Seminole culture is largely derived from that of the Creek; the most important ceremony is the Green Corn Dance; other notable traditions include use of the black drink and ritual tobacco. As the Seminole adapted to Florida environs, they developed local traditions, such as the construction of open-air, thatched-roof houses known as chickees. [3] Historically the Seminole spoke Mikasuki and Creek, both Muskogean languages. The Seminole became increasingly independent of other Creek groups and established their own identity. [5] The tribe expanded considerably during this time, and was further supplemented from the late 18th century by free blacks and escaped slaves who settled near and paid tribute to Seminole towns. The latter became known as Black Seminoles, although they kept their own Gullah culture. The Seminole were first confined to a large inland reservation by the Treaty of Moultrie Creek (1823) and then forcibly evicted from Florida by the Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832). [6] By 1842, most Seminoles and Black Seminoles had been removed to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. During the American Civil War, most Oklahoma Seminole allied with the Confederacy, after which they had to sign a new treaty with the U. Including freedom and tribal membership for the Black Seminole. Today residents of the reservation are enrolled in the federally recognized Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, while others belong to unorganized groups. [7] In the late 19th century, the Florida Seminole re-established limited relations with the U. Government and in 1930 received 5,000 acres (20 km2) of reservation lands. Few Seminole moved to reservations until the 1940s; they reorganized their government and received federal recognition in 1957 as the Seminole Tribe of Florida. The more traditional people near the Tamiami Trail received federal recognition as the Miccosukee Tribe in 1962. Seminole groups in Oklahoma and Florida had little contact with each other until well into the 20th century, but each developed along similar lines as the groups strived to maintain their culture while they struggled economically. Old crafts and traditions were revived in the mid-20th century as Seminoles began seeking tourism dollars when Americans began to travel more on the country’s growing highway system. In the 1970s, Seminole tribes began to run small bingo games on their reservations to raise revenue, winning court challenges to initiate Indian gaming, which many U. Tribes have adopted to generate revenues for welfare, education, and development. Political and social organization. Seminole Tribe of Florida. The word “Seminole” is almost certainly derived from the Creek word simanó-li, which has been variously translated as “frontiersman”, “outcast”, “runaway”, “separatist”, and similar words. More speculatively, the Creek word itself, may be derived from the Spanish word cimarrón, meaning “runaway” or “wild one”, historically used for certain Native American groups in Florida. [10] The people who constituted the nucleus of this Florida group either chose to leave their tribe or were banished. At one time, the terms “renegade” and “outcast” were used to describe this status, but the terms have fallen into disuse because of a negative connotation. They identify themselves as yat’siminoli or “free people” because for centuries their ancestors had resisted Spanish efforts to conquer and convert them, as well as English efforts to take their lands and use them in their wars. [11] They signed several treaties with the United States including the Treaty of Moultrie Creek and the Treaty of Paynes Landing. Native American refugees from northern wars, such as the Yuchi and Yamasee after the Yamasee War in South Carolina, migrated into Spanish Florida in the early 18th century. More arrived in the second half of the 18th century, as the Lower Creeks, part of the Muscogee people, began to migrate from several of their towns into Florida to evade the dominance of the Upper Creeks and pressure of English colonists moving into their lands. [12] They spoke primarily Hitchiti, of which Mikasuki is a dialect, which is the primary traditional language spoken today by Miccosukee in Florida. Joining them were several bands of Choctaw, many of whom were native to western Florida. Chickasaw cultures had also left Georgia due to conflicts with colonists and their Native American allies. [citation needed] Also fleeing to Florida were African-Americans who had escaped from slavery in the English colonies. The new arrivals moved into virtually uninhabited lands that had once been peopled by several cultures indigenous to Florida, such as the Apalachee, Timucua, Calusa, and others. The native population had been devastated by infectious diseases brought by Spanish explorers in the 1500s and later colonization by European settlers. Later, raids by English and Native American slavers destroyed the string of Spanish missions across northern Florida, and most of the survivors left for Cuba when the Spanish withdrew after ceding Florida to the British in 1763, following the French and Indian War. As they established themselves in northern and peninsular Florida throughout the 1700s, the various new arrivals intermingled with each other and with the few remaining indigenous people. In a process of ethnogenesis, they constructed a new culture which they called “Seminole”, a derivative of the Mvskoke’ (a Creek language) word simano-li, an adaptation of the Spanish cimarrón which means “wild” (in their case, “wild men”), or “runaway” [men]. At that time, numerous refugees of the Red Sticks migrated south, adding about 2,000 people to the population. They were Creek-speaking Muscogee, and were the ancestors of most of the later Creek-speaking Seminole. [14] In addition, a few hundred escaped African-American slaves (known as the Black Seminole) had settled near the Seminole towns and, to a lesser extent, Native Americans from other tribes, and some white Americans. The unified Seminole spoke two languages: Creek and Mikasuki (mutually intelligible with its dialect Hitchiti), [15] two among the Muskogean languages family. Creek became the dominant language for political and social discourse, so Mikasuki speakers learned it if participating in high-level negotiations. The Muskogean language group includes Choctaw and Chickasaw, associated with two other major Southeastern tribes. During the colonial years, the Seminole were on good terms with both the Spanish and the British. In 1784, after the American Revolutionary War, Britain came to a settlement with Spain and transferred East and West Florida to it. The Spanish Empire’s decline enabled the Seminole to settle more deeply into Florida. They were led by a dynasty of chiefs of the Alachua chiefdom, founded in eastern Florida in the 18th century by Cowkeeper. Beginning in 1825, Micanopy was the principal chief of the unified Seminole, until his death in 1849, after Removal to Indian Territory. [16] This chiefly dynasty lasted past Removal, when the US forced the majority of Seminole to move from Florida to the Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma) after the Second Seminole War. Micanopy’s sister’s son, John Jumper, succeeded him in 1849 and, after his death in 1853, his brother Jim Jumper became principal chief. He was in power through the American Civil War, after which the US government began to interfere with tribal government, supporting its own candidate for chief. After the independent United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1821, [17] white settlers increased political and governmental pressure on the Seminole to move and give up their lands. “The Seminoles were victims of a system that often blatantly favored whites”[18]. [6] By 1842, most Seminoles and Black Seminoles had been coerced or forced to move to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. During the American Civil War, most of the Oklahoma Seminole allied with the Confederacy, after which they had to sign a new treaty with the U. The Oklahoma and Florida Seminole filed land claim suits in the 1950s, which were combined in the government’s settlement of 1976. The tribes and Traditionals took until 1990 to negotiate an agreement as to division of the settlement, a judgment trust against which members can draw for education and other benefits. The Florida Seminole founded a high-stakes bingo game on their reservation in the late 1970s, winning court challenges to initiate Indian Gaming, which many tribes have adopted to generate revenues for welfare, education and development. The Seminole were organized around itálwa, the basis of their social, political and ritual systems, and roughly equivalent to towns or bands in English. Membership was matrilineal but males held the leading political and social positions. Each itálwa had civil, military and religious leaders; they were self-governing throughout the nineteenth century, but would cooperate for mutual defense. The itálwa continued to be the basis of Seminole society in the West into the 21st century. Main article: Seminole Wars. Coeehajo, Chief, 1837, Smithsonian American Art Museum. After attacks by Spanish colonists on American Indian towns, Natives began raiding Georgia settlements, purportedly at the behest of the Spanish. The Seminoles always accepted blacks and intermarried with former slaves as they escaped slavery. This angered the plantation owners. In the early 19th century, the U. Army made increasingly frequent invasions of Spanish territory to recapture escaped slaves. Following the war, the United States effectively controlled East Florida. In 1819 the United States and Spain signed the Adams-Onís Treaty, [22] which took effect in 1821. Andrew Jackson was named military governor of Florida. As European-American colonization increased after the treaty, colonists pressured the Federal government to remove Natives from Florida. Slaveholders resented that tribes harbored runaway Black slaves, and more colonists wanted access to desirable lands held by Native Americans. Sign at Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park commemorating hundreds of African-American slaves who escaped to freedom in the early 1820s in the Bahamas. After acquisition by the U. Of Florida in 1821, many American slaves and Black Seminoles frequently escaped from Cape Florida to the British colony of the Bahamas, settling mostly on Andros Island. Contemporary accounts noted a group of 120 migrating in 1821, and a much larger group of 300 African-American slaves escaping in 1823, picked up by Bahamians in 27 sloops and also by canoes. [24] They developed a village known as Red Bays on Andros. [25] Federal construction and staffing of the Cape Florida Lighthouse in 1825 reduced the number of slave escapes from this site. Cape Florida and Red Bays are sites on the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Trail. Under colonists’ pressure, the US government made the 1823 Treaty of Camp Moultrie with the Seminole, seizing 24 million acres in northern Florida[26] and offering them a greatly reduced reservation in the Everglades of about 100,000-acre (400 km2). [27] They and the Black Seminoles moved into central and southern Florida. In 1832, the United States government signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing with a few of the Seminole chiefs. They promised lands west of the Mississippi River if the chiefs agreed to leave Florida voluntarily with their people. The Seminoles who remained prepared for war. White colonists continued to press for their removal. In 1835, the U. Army arrived to enforce the treaty. The Seminole leader Osceola led the vastly outnumbered resistance during the Second Seminole War. Drawing on a population of about 4,000 Seminole and 800 allied Black Seminoles, he mustered at most 1,400 warriors (Andrew Jackson estimated they had only 900). They countered combined U. Army and militia forces that ranged from 6,000 troops at the outset to 9,000 at the peak of deployment in 1837. To survive, the Seminole allies employed guerrilla tactics with devastating effect against U. Forces, as they knew how to move within the Everglades and use this area for their protection. Osceola was arrested (in a breach of honor) when he came under a flag of truce to negotiations with the US in 1837. He died in jail less than a year later. He was decapitated, his body buried without his head. Other war chiefs, such as Halleck Tustenuggee and John Jumper, and the Black Seminoles Abraham and John Horse, continued the Seminole resistance against the army. After a full decade of fighting, the war ended in 1842. Scholars estimate the U. An estimated 3,000 Seminole and 800 Black Seminole were forcibly exiled to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi, where they were settled on the Creek reservation. A few hundred survivors retreated into the Everglades. In the end, after the Third Seminole War, the government gave up trying to subjugate the Seminole and left the estimated fewer than 500 survivors in peace. Several treaties seem to bear the mark of representatives of the Seminole tribe, [30] including the Treaty of Moultrie Creek and the Treaty of Payne’s Landing. Some claim that the Florida Seminole are the only tribe in America to have never signed a peace treaty with the U. Historically, the various groups of Seminole spoke two mutually unintelligible Muskogean languages: Mikasuki (and its dialect, Hitchiti) and Creek. Mikasuki is now restricted to Florida, where it was the native language of 1,600 people as of 2000. The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is working to revive the use of Creek, which was the dominant language of politics and social discourse, among its people. Creek is spoken by some Oklahoma Seminole and about 200 older Florida Seminole (the youngest native speaker was born in 1960). Today English is the predominant language among both Oklahoma and Florida Seminole, particularly the younger generations. Most Mikasuki speakers are bilingual. The Seminole use Cirsium horridulum to make blowgun darts. Main article: Seminole music. Seminole woman painted by George Catlin 1834. During the Seminole Wars, the Seminole people began to separate due to the conflict and differences in ideology. The Seminole population had also been growing significantly, though it was diminished by the wars. [33] With the division of the Seminole population between Oklahoma and Florida, some traditions such as powwow trails and ceremonies were maintained among them. In general, the cultures grew apart and had little contact for a century. The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, and the Seminole Tribe of Florida and Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, described below, are federally recognized, independent nations that operate in their own spheres. Seminole tribes generally follow Christianity, both Protestantism and Roman Catholicism, and their traditional Native religion, which is expressed through the stomp dance and the Green Corn Ceremony held at their ceremonial grounds. Indigenous peoples have practiced Green Corn rituals for centuries. Contemporary southeastern Native American tribes, such as the Seminole and Muscogee Creek, still practice these ceremonies. As converted Christian Seminoles established their own churches, they incorporated their traditions and beliefs into a syncretic indigenous-Western practice. [35] One example is, Seminole hymns sung in the indigenous (Muscogee) language, inclusive of key Muscogee language terms (for example, the Muscogee term “mekko” or chief conflates with “Jesus”) and the practice of a song leader (an indigenous song practice) are common. In the 1950s, federal projects in Florida encouraged the tribe’s reorganization. They created organizations within tribal governance to promote modernization. As Christian pastors began preaching on reservations, Green Corn Ceremony attendance decreased. This created tension between religiously traditional Seminole and those who began adopting Christianity. In the 1960s and 1970s, some tribal members on reservations, such as the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation in Florida, viewed organized Christianity as a threat to their traditions. By the 1980s, Seminole communities were concerned about loss of language and tradition. Many tribal members began to revive the observance of traditional Green Corn Dance ceremonies, and some moved away from Christianity observance. By 2000 religious tension between Green Corn Dance attendees and Christians (particularly Baptists) decreased. Some Seminole families participate in both religions; these practitioners have developed a Christianity that has absorbed some tribal traditions. In 1946 the Department of Interior established the Indian Claims Commission, to consider compensation for tribes that claimed their lands were seized by the federal government during times of conflict. Tribes seeking settlements had to file claims by August 1961, and both the Oklahoma and Florida Seminoles did so. It had established that, at the time of the 1823 Treaty of Moultrie Creek, the Seminole exclusively occupied and used 24 million acres in Florida, which they ceded under the treaty. [26] Assuming that most blacks in Florida were escaped slaves, the United States did not recognize the Black Seminoles as legally members of the tribe, nor as free in Florida under Spanish rule. Although the Black Seminoles also owned or controlled land that was seized in this cession, they were not acknowledged in the treaty. In 1976 the groups struggled on allocation of funds among the Oklahoma and Florida tribes. Based on early 20th-century population records, at which time most of the people were full-blood, the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma was to receive three-quarters of the judgment and the Florida peoples one-quarter. The federal government put the settlement in trust until the court cases could be decided. The Oklahoma and Florida tribes entered negotiations, which was their first sustained contact in the more than a century since removal. In 1990 the settlement was awarded: three-quarters to the Seminole Tribe of Oklahoma and one-quarter to the Seminole of Florida, including the Miccosukee. [38] The tribes have set up judgment trusts, which fund programs to benefit their people, such as education and health. Main article: Seminole Nation of Oklahoma. [39] During the American Civil War, the members and leaders split over their loyalties, with John Chupco refusing to sign a treaty with the Confederacy. The split among the Seminole lasted until 1872. After the war, the United States government negotiated only with the loyal Seminole, requiring the tribe to make a new peace treaty to cover those who allied with the Confederacy, to emancipate the slaves, and to extend tribal citizenship to those freedmen who chose to stay in Seminole territory. The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma now has about 16,000 enrolled members, who are divided into a total of fourteen bands; for the Seminole members, these are similar to tribal clans. The Seminole have a society based on a matrilineal kinship system of descent and inheritance: children are born into their mother’s band and derive their status from her people. To the end of the nineteenth century, they spoke mostly Mikasuki and Creek. Two of the fourteen are “Freedmen Bands, ” composed of members descended from Black Seminoles, who were legally freed by the US and tribal nations after the Civil War. They have a tradition of extended patriarchal families in close communities. While the elite interacted with the Seminole, most of the Freedmen were involved most closely with other Freedmen. They maintained their own culture, religion and social relationships. At the turn of the 20th century, they still spoke mostly Afro-Seminole Creole, a language developed in Florida related to other African-based Creole languages. The Nation is ruled by an elected council, with two members from each of the fourteen bands, including the Freedmen’s bands. The capital is at Wewoka, Oklahoma. The Seminole Nation of Oklahoma has had tribal citizenship disputes related to the Seminole Freedmen, both in terms of their sharing in a judgment trust awarded in settlement of a land claim suit, and their membership in the Nation. Seminole family of tribal elder, Cypress Tiger, at their camp near Kendall, Florida, 1916. Photo taken by botanist, John Kunkel Small. The remaining few hundred Seminoles survived in the Florida swamplands, avoiding removal. They lived in the Everglades, to isolate themselves from European-Americans. Seminoles continued their distinctive life, such as clan-based matrilocal residence in scattered thatched-roof chickee camps. [39] Today, the Florida Seminole proudly note the fact that their ancestors were never conquered. In the 20th century before World War II, the Seminole in Florida divided into two groups; those who were more traditional and those willing to adapt to the reservations. Those who accepted reservation lands and made adaptations achieved federal recognition in 1957 as the Seminole Tribe of Florida. Those who had kept to traditional ways and spoke the Mikasuki language organized as the Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, gaining state recognition in 1957 and federal recognition in 1962. See also Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida, below. With federal recognition, they gained reservation lands and worked out a separate arrangement with the state for control of extensive wetlands. Other Seminoles not affiliated with either of the federally recognized groups are known as Traditional or Independent Seminoles. At the time the tribes were recognized, in 1957 and 1962, respectively, they entered into agreements with the US government confirming their sovereignty over tribal lands. Main article: Seminole Tribe of Florida. Seminole patchwork shawl made by Susie Cypress from Big Cypress Indian Reservation, ca. The Seminole worked hard to adapt, but they were highly affected by the rapidly changing American environment. Natural disasters magnified changes from the governmental drainage project of the Everglades. Residential, agricultural and business development changed the “natural, social, political, and economic environment” of the Seminole. [34] In the 1930s, the Seminole slowly began to move onto federally designated reservation lands within the region. [41] Initially, few Seminoles had any interest in moving to the reservation land or in establishing more formal relations with the government. Some feared that if they moved onto reservations, they would be forced to move to Oklahoma. Others accepted the move in hopes of stability, jobs promised by the Indian New Deal, or as new converts to Christianity. Seminoles’ Thanksgiving meal mid-1950s. Beginning in the 1940s, however, more Seminoles began to move to the reservations. A major catalyst for this was the conversion of many Seminole to Christianity, following missionary effort spearheaded by the Creek Baptist evangelist Stanley Smith. For the new converts, relocating to the reservations afforded them the opportunity to establish their own churches, where they adapted traditions to incorporate into their style of Christianity. [43] Reservation Seminoles began forming tribal governments and forming ties with the Bureau of Indian Affairs. [43] In 1957 the nation reorganized and established formal relations with the US government as the Seminole Tribe of Florida. [34] The Seminole Tribe of Florida is headquartered in Hollywood, Florida. They control several reservations: Big Cypress, Brighton Reservation, Fort Pierce Reservation, Hollywood Reservation, Immokalee Reservation, and Tampa Reservation. A traditional group who became known as the Trail Indians moved their camps closer to the Tamiami Trail connecting Tampa and Miami, where they could sell crafts to travelers. They felt disfranchised by the move of the Seminole to reservations, who they felt were adapting too many European-American ways. Their differences were exacerbated in 1950 when some reservation Seminoles filed a land claim suit against the federal government for seizure of lands in the 19th century, an action not supported by the Trail Indians. Following federal recognition of the Seminole Tribe of Florida in 1957, the Trail Indians decided to organize a separate government. They sought recognition as the Miccosukee Tribe, as they spoke the Mikasuki language. They received federal recognition in 1962, and received their own reservation lands, collectively known as the Miccosukee Indian Reservation. [8] The Miccosukee Tribe set up a 333-acre (1.35 km2) reservation on the northern border of Everglades National Park, about 45 miles (72 km) west of Miami. In the United States 2000 Census, 12,431 people self-reported as Seminole American. An additional 15,000 people identified as Seminole in combination with some other tribal affiliation or race. A Seminole spearing a garfish from a dugout, Florida, 1930. The Seminole in Florida have been engaged in stock raising since the mid-1930s, when they received cattle from western Native Americans. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) hoped that the cattle raising would teach Seminoles to become citizens by adapting to agricultural settlements. The BIA also hoped that this program would lead to Seminole self-sufficiency. Cattle owners realized that by using their cattle as equity, they could engage in “new capital-intensive pursuits”, such as housing. Since then, the two Florida tribes have developed economies based chiefly on sales of duty-free tobacco, heritage and resort tourism, and gambling. They had previously licensed it for several of their casinos. From beginnings in the 1930s during the Great Depression, the Seminole Tribe of Florida today owns one of the largest cattle operations in Florida, and the 12th largest in the nation. Florida experienced a population boom in the early 20th century when the Flagler railroad to Miami was completed. The state became a growing destination for tourists and many resort towns were developed. [39] In the years that followed, many Seminoles worked in the cultural tourism trade. By the 1920s, many Seminoles were involved in service jobs. Some of the crafts included woodcarving, basket weaving, beadworking, patchworking, and palmetto-doll making. These crafts are still practiced today. Fewer Seminole rely on crafts for income because gaming has become so lucrative. [34] The Miccosukee Tribe earns revenue by owning and operating a casino, resort, a golf club, several museum attractions, and the “Indian Village”. At the “Indian Village”, Miccosukee demonstrate traditional, pre-contact lifestyles to educate people about their culture. In 1979, the Seminoles opened the first casino on Indian land, ushering in what has become a multibillion-dollar industry operated by numerous tribes nationwide. [49] This casino was the first tribally operated bingo hall in North America. Since its establishment, gaming has become an important source of revenue for tribal governments. [50] In more recent years, income from the gaming industry has funded major economic projects such as sugarcane fields, citrus groves, cattle, ecotourism, and commercial agriculture. The Seminole are reflected in numerous Florida place names. Seminole, a city in Pinellas County. Seminole, a small community in Okaloosa County. Historic Seminole Heights, a residential district in Tampa, Florida. There is also a Seminole County in Oklahoma, and a Seminole County in the southwest corner of Georgia (separated from Florida by Lake Seminole). Florida State Seminoles, athletic teams of Florida State University. SEMINOLE LIGHT HORSE POLICE. Organization of the Seminole Light-Horse. Seminole Agent Samuel M. Rutherford reported on August 29, 1859, that the Seminoles had no national fund to defray the expenses of government, and as a consequence there was a great laxity in the executions of the laws; that these Indians needed an efficient “Light-Horse” to execute their laws and if those officers were expected to perform their duty, they must be paid. The funds could be withdrawn from the annuity and used for that purpose. Evidently no move was made at that time to establish the Light-Horse. The Civil War was on the horizon before the Seminoles were well established in their new home after their removal from Florida, and all efforts at carrying on any government among them was destined to await the end of the conflict. They maintained law and order, and like the celebrated Canadian “Mounties, ” they always got their man. Teague at the age of nineteen, arrived in the Indian Territory from Fort Worth, Texas in 1876, with a drove of cattle for the Seminole Nation. He decided that he would prefer some other work and he was engaged by Governor John F. Brown of the Seminole Nation as a laborer on his farm for the following nineteen years. The youth evidently proved himself efficient as Governor Brown asked him how he would like to become a light-horseman. “I told him that I couldn’t be a light-horseman, but he said, “Yes you can. You just do what I tell you to do. ” “I said, Yes, but you might tell me to kill a man and I couldn’t do that. ” “He said, Yes, you just kill him if I tell you to. ” ” A light-horseman was just the same as a policeman, so I was made a Light-horseman. Shaw was born November 5, 1860, at Bates, Missouri, arrived at Wewoka in September, 1894. He was employed on trial by Governor Brown for one month and as he gave satisfaction he was given charge of all of the saws and other machinery in the Governor’s mills at Wewoka and Sasakwa. Shaw related that the Seminole Light-Horse numbered about twelve at that time and the captain was Jim Larney. Court was held in the old Council House at Wewoka, and prisoners were punished by the lash law, their feet being tied together with a long pole. The prisoner’s hands were tied together with a long rope thrown over a high limb of a tree and two light-horsemen would then pull the prisoner until his body was stretched to full length and then he would be given his lashes on a bare back. After he was whipped, he would put on his shirt with back bleeding with nothing done for his wounds. Grayson, Henryetta, Oklahoma was of the opinion that Governor Brown was a very smart Indian. Two light-horsemen rode in the wagon, one rode in front, two on each side, and two behind. All were heavily armed and no one ever had the courage to attack them so they always arrived at their destination without trouble. Among other Seminole light-horsemen were Pomp Davis and Caeser Payne who frequently accompanied members of their tribe to Wewoka for trial. Chepon Moses of Wewoka related that when he was a youth he made his home with an uncle of the name of Harrison who was a light-horseman. During a drunken fight between Pul-musky and John Factor the last named was killed, and Pul-musky was sentenced to death. He was freed until the day appointed for his execution and when the time, day, and hour, came the prisoner was here among the crowd and he walked forward. He was blind-folded, and he sat on a rock by a tree: a white paper heart was cut and placed over his heart and then two light-horsemen were selected to shoot him. Bruner and Caeser Payne were the ones and they were negros. Another description of punishment by the light-horsemen was given by John Alexander Frazier of Elk City, Oklahoma. He stated that when he arrived in Wewoka the Seminoles had their own laws and executed their criminals. They brought out an Indian and took off his shirt, then they tied his hands and feet together with ropes. Then these Indians took a long lariat rope and tied him to a rail and took him to a log cabin, the roof of which had almost rotted off, and threw the rope over one end of a log that was sticking out… Two men got on the rail and five or six men got hold of the rope and stretched the criminal up in the air. Then the Indian Chief ordered the light-horse-men all to fall in line and walk up to the criminal. Each light-horseman had a hickory stick three of four feet long in his hand. There were ten light-horsemen in line and the Indian Chief gave orders that they should step up one at a time and each should give the culprit ten licks. If the light-horsemen dropped his whip he had to fall out of line.. Light Horsemen-Seminole Nation – Wewoka, I. Seminole Chief John Chupco (seated center). With the Seminole Council and Light Horse Police. Chapter six of the Seminole Laws, as furnished by the U. Indian inspector for Indian Territory, and translated by G. Grayson, July 1906, contains the following fifteen sections. I The Seminole Nation shall have a force of Light Horsemen. The Company of Light Horse shall consist of one Captain, one Lieutenant, and eight privates, in all, ten men. The Company of Light Horse when installed in office shall serve for the term of four years. If by reason of death, or the violation of any law of the Nation by any member of the Company, his place on the force becomes vacant. It shall be the duty of the National Council to fill such vacancy or make any other arrangement that shall be satisfactory. If any member of the Light-Horse company shall resign his office, the chiefs shall report such resignation to the National Council, when it will become the duty of that body to fill the vacancy. The Light Horse company when in charge of a prisoner under arrest, shall exercise due humanity and care in the treatment accorded him during his imprisonment. If a Light Horsemen shall, through neglect of duty, or flagrant carelessness, suffer a prisoner in his charge to escape from his custody, he shall be deemed guilty. If it shall be proved that any Light Horseman by drinking whisky or any other intoxicant, had become intoxicated, he shall be deemed guilty. Power and authority are hereby vested in the chiefs of the Nation to issue warrant for arrest; and the Light Horsemen shall make no arrests without first having received such warrant from the chiefs. The chiefs shall first be fully satisfied that an act of violence of law has been committed before issuing a warrant for arrest. In making arrests, the Light Horsemen shall exercise due care that no unnecessary physical pain or other injury is inflicted on the person being arrested. If the Light Horseman shall proceed to effect the arrest of any person, abiding by and observing the requirements of the foregoing section of his official acts; and if, notwithstanding the orderly deportment of the officer, the person to be arrested shall make resistance by force of arms, then the arresting officer shall have the right to kill him. Such a killing shall be deemed to be the legitimate result of the operation of law. The Chiefs are hereby authorized to engage a posse to aid the Light-Horse when necessary, who shall be subject to the laws governing the Light-Horsemen. Passed by the National Council January 28th, 1903 OKFUSKEY MILLER, Chairman T. Approved January 28, 1903. HULBUTTA MIKKO, Principal Chief Seminole Nation. THOMAS LITTLE, 2nd Chief, S. Courtesy of Carolyn Thomas Foreman. Last Captain of the Light Horsemen. Names from the past associated with the Seminole Light-horse police include Captain Lonnie, Captain Jacob Harrison, Captain Thomas Cloud and Captain Chili Fish who later refused the office of Chief of the Seminole Nation after Oklahoma statehood. Chilli Fish was the last captain of the Seminole Light-horse police during that era. Other members of the Light-horse included black members of the tribe known as Freedman such as Cumsey Bruner, John Dennis, Tom Payne, Ceasar Payne, Thomas Bruner and Sam Cudgo. The most famous Seminole Freedman Light-horseman was Dennis Cyrus, who served with the Light-horse for twenty-five years. Five of those years, Cyrus held a deputy U. Marshall commission from the U. Marshal John Carroll at Fort Smith, Arkansas. Dennis Cyrus was involved in a shooting altercation in Muskogee in August of 1905. Cyrus was a delegate at a political convention in town. While resting at a rooming house, a fight occurred in the room next door. Mitchell, a prominent businessman in Muskogee was having a fight with a lady friend. During the dispute, Mitchell barged in to Cyrus’ room with a gun in hand. Cyrus told him to drop the weapon. Mitchell hesitated and Cyrus shot him in the right shoulder, Mitchell later recovered from his wound and Cyrus was exonerated of the shooting. At the time of the incident the Muskogee Times Democrat reported that Dennis Cyrus was a posse man for deputy U. Marshal John Cordell, stationed at Wewoka. The Muskogee Cimeter stated: Dennis Cyrus is one of the best officers in the Western District and is always faithful in the performance of duty. Those who know him best know that he is a brave and fearless officer and that he would not injure anyone without permission. During the territorial era of the Indian Territory, the Seminole Nation council served as the court and the chief was the acting judge when criminal cases were adjudicated. The laws in the nation were enforced by the police known as the Light-horse. The Light-horse were the pick of the tribe, the cream of the crop, selected by the council for fearlessness and honesty. Their job was to track down criminals and bring them to the council house in Wewoka. If the need arose the chief could hire “special” Light-Horsemen. In May of 1885, a heavily armed band of white cowboys who worked the Pottawatomie Reservation openly stole sixty head of cattle the belonged to the Seminole Indians. Principal chief John Jumper raised a force of fifty “special” Light-Horse to guard the western border of the nation. Brown, the sub-chief, secured from the Federal authorities an assurance that any whites caught stealing form the Seminoles, and resisting arrest by Seminole Light-horse, could be killed without prosecution for murder by the federal court in Fort Smith. On many occasions the Seminole Light-horse would hold non-citizens for the deputy U. Marshals to take back to the federal jail in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Marshal Bass Reeves picked up many fugitives in this fashion at Wewoka. Killed In The Line Of Duty. Four Seminole Light-horsemen are known to have been killed in the line of duty before Oklahoma statehood. Around 1899, a condemned man failed to show up for his execution. Light-horseman Dickie Lane was sent into the Sasakwa-Konawa area to bring him to Wewoka. Lane was shot attempting to arrest the felon, Lane, though badly hurt, was successful in getting in his wagon and starting back to Wewoka. Lane bled to death before he could reach help. He was found and brought back to the Seminole capitol. Burial took place at Lucenda Coker’s place, but the grave has since been plowed over. Lane was described by his grand-daughter, Maria Hall, as an individual who was slow to anger and one who stood by a person in need. Light-Horse Captain Thomas Cloud. Captain Thomas Cloud and seventeen Light-horsemen, on March 29, 1885, were searching for outlaws in a black settlement on the south side of the Canadian River near Sacred Heart Mission. At the residence of Paro Bruner they found Rector Rogers, who had killed his brother the previous fall in the Creek Nation. Rogers told the posse he was not going to talk to them and slammed the door. Rogers began shooting at the posse from the cabin. Light-horseman Sam Cudgo was hit in the abdomen with a shot from Roger’s rifle. Cudgo died about an hour after being wounded. The posse poured a furious volley of gunfire into the cabin. One of the gunshots from Rogers hit Captain Cloud in the thigh of the left leg, where the bullet shattered the bone. Captain Cloud told his men to not let Rogers escape at any cost. Cudgo’s body was taken to Wewoka, and the seriously wounded Captain Cloud was taken to the home of Seminole chief John Jumper in Sasakwa. On February 3, 1906, Light-horseman Billy Cully was murdered in a shack five miles west of Sasakwa. Three men were implicated in the murder: Alex Harjo, Barney Fixico, and Wild Cat. Cully had been killed by a blow to the head with a blunt instrument. During the previous Christmas, Cully had an altercation with Alex Harjo, so there was bad blood between them. Marshal Bass Reeves immediately recognized Wild Cat as a prisoner who had escaped his custody twenty years earlier. The lawman had presumed Wild Cat was dead. Billy Cully was described as well educated. He was the brother-in-law of Governor Brown. Although the smallest police force of the Five Civilized Tribes in the Indian Territory, the Seminole Light-horse police were the most feared by lawbreakers in the Nations. Their record and dedication to duty is an example of outstanding law enforcement on the Oklahoma Frontier. Interestingly, the term “light-horse” came from Revolutionary War hero General Henry Lee due to his capability of cavalry movements during the conflict, earning him the nickname Light-horse Harry. General Henry Lee was the father of General Robert E. Above Text courtesy of Art T. The Seminoles of Florida call themselves the “Unconquered People, ” descendants of just 300 Indians who managed to elude capture by the U. Army in the 19th century. Today, more than 2,000 live on six reservations in the state – located in Hollywood, Big Cypress, Brighton, Immokalee, Ft. The Seminoles work hard to be economically independent. To do this, they’ve jumped into a number of different industries. Tourism and bingo profits pay for infrastructure and schools on their reservations, while citrus groves and cattle have replaced early 20th-century trade in animal hides and crafts as the tribe’s primary revenue sources. While becoming more economically diverse, the Seminoles also maintain respect for the old ways. Some still live in open, palm-thatched dwellings called chickees, wear clothing that is an evolution of traditional styles, and some celebrate the passing of the seasons just as their ancestors did more than two centuries ago. They also visit schools and festivals across the state, performing traditional dance and music to share their history with non-Indians. Creeks Migrate to Florida. Seminole history begins with bands of Creek Indians from Georgia and Alabama who migrated to Florida in the 1700s. Conflicts with Europeans and other tribes caused them to seek new lands to live in peace. Groups of Lower Creeks moved to Florida to get away from the dominance of Upper Creeks. Some Creeks were searching for rich, new fields to plant corn, beans and other crops. For a while, Spain even encouraged these migrations to help provide a buffer between Florida and the British colonies. The 1770s is when Florida Indians collectively became known as Seminole, a name meaning “wild people” or runaway. In addition to Creeks, Seminoles included Yuchis, Yamasses and a few aboriginal remnants. The population also increased with runaway slaves who found refuge among the Indians. At war with the U. OsceolaRun-ins with white settlers were becoming more regular by the turn of the century. Settlers wanted Indian land and their former slaves back. In 1817, these conflicts escalated into the first of three wars against the United States. President Andrew Jackson invaded then-Spanish Florida, attacked several key locations, and pushed the Seminoles farther south into Florida. After passage of the Indian Removal Act in 1830, the U. Government attempted to relocate Seminoles to Oklahoma, causing yet another war — the Second Seminole War. After defeating the U. In early battles of the Second Seminole War, Seminole leader Osceola was captured by the United States in Oct. 20, 1837, when U. Troops said they wanted a truce to talk peace. By May 8, 1858, when the United States declared an end to conflicts in the third war with the Seminoles, more than 3,000 of them had been moved west of the Mississippi River. That left roughly 200 to 300 Seminoles remaining in Florida, hidden in the swamps. For the next two decades, little was seen of Florida Seminole. At least not until trading posts opened in late 19th century at Fort Lauderdale, Chokoloskee and other places, that’s when some Seminoles began venturing out to trade. Seminoles gain more independence. In the late 1950s, a push among Indian tribes to organize themselves and draft their own charter began — this came as a result of federal legislation which allowed Indian reservations to act as entities separate from the state governments in which they were located. The Seminole tribe improved their independence by adopting a constitutional form of government. This allowed them to act more independently. So on July 21, 1957, tribal members voted in favor of a Seminole Constitution which established the federally recognized Seminole Tribe of Florida.