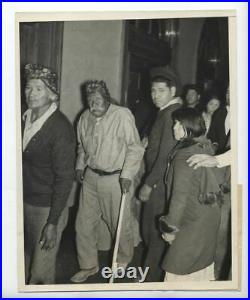

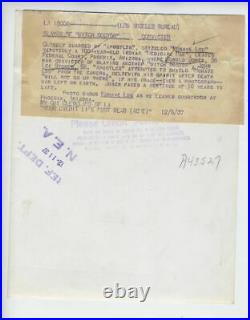

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 1937 PHOTO MEASURING APPROXIMATELY 7 X 9 INCHES OF MOHAVE JOE 100 YEAR OLD INDIAN MEDICINE MAN LEAVING FEDERAL COURT PHOENIX ARIZONA WHERE RONALD JONES, 36 WAS CONVICTED OF SLAYING ANOTHER WITCH DOCTOR, JOHN LEE STOKES. An extraordinary story I wish I knew more about. Press photos here from 1937 show Ronald Jones, age 37, a Mohave Indian (or member of the Yuma tribe, both have roots in the area now known as Colorado) as he was awaiting his trial for murder. Typical saturday night fight on the Rez? Jones defense claims the murdered person, John Lee Stokes, age 68, was a witch. That’s right, a witch doctor. He had apparently bewitched others on the reservation near Parker, Arizona as well. I was able to locate a subsequent article in the LA Times which indicates Ronald Jones accepted a 12 year sentence. I can not find that he was released after completing his sentence. The handwritten note on the reverse of the photo indicates he “hacked” his fellow tribesman to death. Shamanism was a spiritual practice of many, if not all of the original Americans but I certainly don’t know the Shamanistic characteristics of the tribe here. Nor do i have any idea how the Justice system of the United States prosecuted a member of First Peoples outside of their own system of justice. Here is a big plate of story for you. Pair of small press photos, original, dated 1937 Collection Jim Linderman. NOTE: an informed reader sent the following: It does not address this particular case, which is so interesting as the murder of a presumable tribal leader was involved? But he covers the general rules of reservation law. I refer you to a U. Department of Justice publication, Policing on American Indian Reservations. Having grown up in New Mexico, I was taught the basics of reservation justice during my junior high school days (New Mexico History) due to the many reservations in the state. I refer you to chapter 2, page 9 (pdf page 21) of the DoJ document above. Tribal justice systems only have jurisdiction over crimes committed on tribal lands. The offender must be an American Indian (although there are exemptions). Finally, the crime can’t be a serious one like murder. For major crimes, e. Felonies, the Federal system has jurisdiction, not tribal courts or police. The laws cited include the Major Crimes Act of 1885 and the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. Indians in the U. Are dual citizens, not sole citizens of a separate sovereign nation. Indeed, Chief Justice Marshall referred to Indian nations as semisovereign or “domestic dependent nations” in 1831. Indian nations are U. Citizens at their root. This is how they can, and are, appropriately, subject to the U. Indian Killer Gets 12 Years Ronald Jones, Mohave Indian yesterday was sentenced by Dave W. Ling, United States district judge, to serve 12 years in a fed eral penitentiary for the bizarre “witchcraft” slaying of John Lee Stokes. Primitive superstitions and black magic constantly were brought into tne limelight m the brief trial, which was climaxed December 5 by Jones’ conviction of second degree murder. Is Impassive As he was sentenced yesterday, Jones presented the same impassive front to the court that he present ed all through the trial. Not once from the very beginning did his face show a trace of emotion and he seemed uninterested in the proceedings. He had seldom paid much attention to examination when on the stand during the trial and frequently had had to be asked questions a second time. Fellow tribesmen went to the courtroom to hear sentence pronounced. Many of them had been witnesses in the trial and had de- clared that John Lee Stokes, whom Jones was convicted of killing, was a “medicine man” and that they were sure Jones had committed the crime because he believed that to be true. Defense attorneys attempted to suDDort this theory and tried to show that to Jones way of thinking the killing was only self-defense. The Jury of 12 white men failed to concede this theory and found Jones guilty. Trial Was Bizarre The trial was colorful and one of the most bizarre in the history of the state, with men stating on the stand they were “medicine men and made their living in that profession”. “Mohave Lou” Beck, said to be more than 100 years old, was one of two professed workers of spells, Jones will be taken to McNeil Island penitentiary this morning by J. Lon Jordan, deputy u. A medicine man or medicine woman is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of indigenous people of the Americas. Individual cultures have their own names, in their respective Indigenous languages, for the spiritual healers and ceremonial leaders in their particular cultures. The medicine man and woman in North America. In the ceremonial context of Indigenous North American communities, “medicine” usually refers to spiritual healing. Medicine men/women should not be confused with those who employ Native American ethnobotany, a practice that is very common in a large number of Native American and First Nations households. The terms “medicine people” or “ceremonial people” are sometimes used in Native American and First Nations communities, for example, when Arwen Nuttall (Cherokee) of the National Museum of the American Indian writes, The knowledge possessed by medicine people is privileged, and it often remains in particular families. Native Americans tend to be quite reluctant to discuss issues about medicine or medicine people with non-Indians. In some cultures, the people will not even discuss these matters with Indians from other tribes. In most tribes, medicine elders are prohibited from advertising or introducing themselves as such. As Nuttall writes, An inquiry to a Native person about religious beliefs or ceremonies is often viewed with suspicion. “[5] One example of this is the Apache medicine cord or Izze-kloth whose purpose and use by Apache medicine elders was a mystery to nineteenth century ethnologists because “the Apache look upon these cords as so sacred that strangers are not allowed to see them, much less handle them or talk about them. The 1954 version of Webster’s New World Dictionary of the American Language reflects the poorly-grounded perceptions of the people whose use of the term effectively defined it for the people of that time: a man supposed to have supernatural powers of curing disease and controlling spirits. ” In effect, such definitions were not explanations of what these “medicine people are to their own communities but instead reported on the consensus of socially and psychologically remote observers when they tried to categorize the individuals. [citation needed] The term “medicine man/woman, ” like the term “shaman, ” has been criticized by Native Americans, as well as other specialists in the fields of religion and anthropology. While non-Native anthropologists sometimes use the term “shaman” for Indigenous healers worldwide, including the Americas, “shaman” is the specific name for a spiritual mediator from the Tungusic peoples of Siberia[7] and is not used in Native American or First Nations communities. The term “medicine man/woman” has also frequently been used by Europeans to refer to African traditional healers, along with the offensive term “witch doctors”. There are many fraudulent healers and scam artists who pose as Cherokee “shamans”, and the Cherokee Nation has had to speak out against these people, even forming a task force to handle the issue. In order to seek help from a Cherokee medicine person a person needs to know someone in the community who can vouch for them and provide a referral. Usually one makes contact through a relative who knows the healer. The Medicine Man, an 1899 sculpture by Cyrus Dallin exhibited in Philadelphia. Bomoh or Dukun in South-East Asia. Mohave or Mojave (Pronounced “Moh-ha-vee”)(Mojave:’Aha Makhav) are a Native American people indigenous to the Colorado River in the Mojave Desert. The Fort Mojave Indian Reservation includes territory within the borders of California, Arizona, and Nevada. The Colorado River Indian Reservation includes parts of California and Arizona and is shared by members of the Chemehuevi, Hopi, and Navajo peoples. The original Colorado River and Fort Mojave reservations were established in 1865 and 1870, respectively. Both reservations include substantial senior water rights in the Colorado River; water is drawn for use in irrigated farming. The four combined tribes sharing the Colorado River Indian Reservation function today as one geo-political unit known as the federally recognized Colorado River Indian Tribes; each tribe also continues to maintain and observe its individual traditions, distinct religions, and culturally unique identities. Mohave ceramic figurine with red slip and earrings, pre-1912, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. In the 1930s, George Devereux, a Hungarian-French anthropologist, did fieldwork and lived among the Mohave for an extended period of study. He published extensively about their culture and incorporated psychoanalytic thinking in his interpretation of their culture. The Mojave language belongs to the River Yuman branch of the Yuman language family. In 1994 approximately 75 people in total on the Colorado River and Fort Mojave reservations spoke the language, according to linguist Leanne Hinton. The tribe has published language materials, and there are new efforts to teach the language to their children. The Mohave creator is Matevilya, who gave the people their names and their commandments. His son is Mastamho, who gave them the River and taught them how to plant. They have traditionally used the indigenous plant Datura as a deliriant hallucinogen in a religious sacrament. A Mohave who is coming of age must consume the plant in a rite of passage, in order to enter a new state of consciousness. 1851 drawing of Mohavi men and women made by Lorenzo Sitgreaves’ topographical mission across Arizona in 1851. Chiefs Irataba and Cairook, with Mohave woman, by Balduin Möllhausen (1856). Much of early Mojave history remains unrecorded in writing, since the Mojave language was not written in precolonial times. They depended on oral communication to transmit their history and culture from one generation to the next. Disease, outside cultures and encroachment on their territory disrupted their social organization. Together with having to adapt to a majority culture of another language, this resulted in interrupting the Mojave transmission of their stories and songs to the following generations. The tribal name has been spelled in Spanish and English transliteration in more than 50 variations, such as Hamock avi, Amacava, A-mac-ha ves, A-moc-ha-ve, Jamajabs, and Hamakhav. This has led to misinterpretations of the tribal name, also partly traced to a translation error in Frederick W. Hodge’s 1917 Handbook of the American Indians North of Mexico (1917). This incorrectly defined the name Mohave as being derived from hamock, (three), and avi, (mountain). According to this source, the name refers to the mountain peaks known as The Needles in English, located near the Colorado River. (The city of Needles, California is located a few miles north from here). But, the Mojave call these peaks Huukyámpve[4], which means “where the battle took place, ” referring to the battle in which the God-son, Mastamho, slew the sea serpent. [This quote needs a citation]. The Mojave held lands along the river that stretched from Black Canyon, where the tall pillars of First House of Mutavilya loomed above the river, past Avi kwame or Spirit Mountain, the center of spiritual things, to the Quechan Valley, where the lands of other tribes began. As related to contemporary landmarks, their lands began in the north at Hoover Dam and ended about one hundred miles below Parker Dam on the Colorado River, or aha kwahwat in Mojave. Mosa (Mojave girl), 1903, photograph by Edward Curtis. In mid-April 1859, United States troops, led by Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman, on the Expedition of the Colorado, moved upriver into Mojave country with the well-publicized objective of establishing a military post. By this time, white immigrants and settlers had begun to encroach on Mojave lands and the post was intended to protect east-west European-American emigrants from attack by the Mojave. Hoffman sent couriers among the tribes, warning that the post would be gained by force if they or their allies chose to resist. During this period, several members of the Rose party were massacred by the Mojave. The Mojave warriors withdrew as Hoffman’s armada approached and the army, without conflict, occupied land near the future Fort Mojave. Hoffman ordered the Mojave men to assemble on April 23, 1859 at the armed stockade adjacent to his headquarters, to hear Hoffman’ terms of peace. Hoffman gave them the choice of submission or extermination and the Mojave chose submission. At that time the Mojave population was estimated to be about 4,000 which were comprised into 22 clans identified by totems. Two Mojave girls standing in front of a small dwelling with a thatched roof, 1900. Under American law the Mohave were to live on the Colorado River Reservation after its establishment in 1865; however many refused to leave their ancestral homes in the Mojave Valley. At this time, under jurisdiction of the War Department, officials declined to try to force them onto the reservation and the Mojave in the area were relatively free to follow their tribal ways. In the midsummer of 1890, after the end of the Indian Wars, the War Department withdrew its troops and the post was transferred to the Office of Indian Affairs within the Department of the Interior. Beginning in August 1890, the Office of Indian Affairs began an intensive program of assimilation where Mohave, and other native children living on reservations, were forced into boarding schools in which they learned to speak, write, and read English. This assimilation program, which was Federal policy, was based on the belief that this was the only way native peoples could survive. Fort Mojave was converted into a boarding school for local children and other “non-reservation” Indians. Until 1931, forty-one years later, all Fort Mojave boys and girls between the ages of six and eighteen were compelled to live at this school or to attend an advanced Indian boarding school far removed from Fort Mojave. Two Mojave Indian women playing a game fortune-telling with bones? The assimilation helped to break up tribal culture and governments. Such corporal punishment of children scandalized the Mojave, who did not discipline their children in that way. As part of the assimilation the administrators assigned English names to the children and registered as members of one of two tribes, the Mojave Tribe on the Colorado River Reservation and the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe on the Fort Mojave Indian Reservation. These divisions did not reflect the traditional Mojave clan and kinship system. By the late 1960s, thirty years after the end of the assimilation program 18 of the 22 traditional clans had survived. Estimates of the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Kroeber (1925:883) put the 1770 population of the Mohave at 3,000 and Francisco Garcés, a Franciscan missionary-explorer, also estimated the population at 3,000 in 1776Garcés 1900(2):450. Kroeber estimate of the population in 1910 was 1,050. [5] By 1963 Lorraine M. Sherer’s research revealed the population had shrunk to approximately 988, with 438 at Fort Mojave and 550 of the Colorado River Reservation. The Mohave, along with the Chemehuevi, some Hopi, and some Navajo, share the Colorado River Indian Reservation and function today as one geopolitical unit known as the federally recognized Colorado River Indian Tribes; each tribe also continues to maintain and observe its individual traditions, distinct religions, and culturally unique identities. The Colorado River Indian Tribes headquarters, library and museum are in Parker, Arizona, about 40 miles (64 km) north of I-10. The Colorado River Indian Tribes Native American Days Fair & Expo is held annually in Parker, from Thursday through Sunday during the first week of October. The Megathrow Traditional Bird Singing & Dancing social event is also celebrated annually, on the third weekend of March. RV facilities are available along the Colorado River. Mojave, also spelled Mohave, Yuman-speaking North American Indian farmers of the Mojave Desert who traditionally resided along the lower Colorado River in what are now the U. States of Arizona and California and in Mexico. This valley was a patch of green surrounded by barren desert and was subject to an annual flood that left a large deposit of fertile silt. Traditionally, planting began as soon as the floodwaters receded. Unlike some of the desert farmers to the east, whose agricultural endeavours were surrounded by considerable ritual intended to ensure success, the Mojave almost totally ignored rituals associated with crops. In addition to farming, the Mojave engaged in considerable fishing, hunting, and gathering of wild plants. The essential social units among the Mojave were the family and the patrilineage. Hamlets were built wherever there was suitable land for farming, and the fields were owned by the people who cleared them. Formal government among the Mojave consisted mainly of a hereditary tribal chief who functioned as a leader and adviser. Although they did not live in concentrated settlements, the Mojave possessed a strong national identity that became most evident in times of war; as male prestige was based on success and bravery in battle, all able-bodied men generally took part in military activities, which were typically led by a single war chief. The usual enemies of the Mojave were other riverine Yuman peoples, except for the Yuma proper, who were their trusted allies during conflicts. Each combatant generally specialized in or was assigned a single kind of weaponry; battles included archers, clubbers, and stick men and were often highly stylized. In religion the Mojave believed in a supreme creator and attached great significance to dreams, which were considered the source of special powers. Public ceremonies included the singing of cycles of dreamed songs that recited myths; usually the narrative retold a mythic or legendary journey, and some cycles consisted of hundreds of songs. The Quechan (or Yuma) (Quechan: Kwtsaan’those who descended’) are an aboriginal American tribe who live on the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation on the lower Colorado River in Arizona and California just north of the Mexican border. Members are enrolled into the Quechan Tribe of the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation. The federally recognized Quechan tribe’s main office is located in Winterhaven, California. Its operations and the majority of its reservation land are located in California, United States. Fort Yuma Native American Reservation. Cameron Chino, Quechan artist[2]. The first significant contact of the Quechan with Europeans was with the Spanish explorer Juan Bautista de Anza and his party in the winter of 1774. On Anza’s return from his second trip to Alta California in 1776, the chief of the tribe and three of his men journeyed to Mexico City to petition the Viceroy of New Spain for the establishment of a mission. The chief Palma and his three companions were baptized in Mexico City on February 13, 1777. Palma was given the Spanish baptismal name Salvador Carlos Antonio. Spanish settlement among the Quechan did not go smoothly; the tribe rebelled from July 17-19, 1781 and killed four priests and thirty soldiers. They also attacked and damaged the Spanish mission settlements of San Pedro y San Pablo de Bicuñer and Puerto de Purísima Concepción, killing many. The following year, the Spanish retaliated with military action against the tribe. After the United States annexed the territories after winning the Mexican-American War, it engaged in the Yuma War from 1850 to 1853. During which, the historic Fort Yuma was built across the Colorado River from the present day Yuma, Arizona. Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially (see population of Native California). Kroeber (1925:883) put the 1770 population of the Quechan at 2,500. Forbes (1965:341-343) compiled historical estimates and suggested that before they were first contacted, the Quechan had numbered 4,000 or a few more. Kroeber estimated the population of the Quechan in 1910 as 750. By 1950, there were reported to be just under 1,000 Quechan living on the reservation and more than 1,100 off it (Forbes 1965:343). The 2000 census reported a resident population of 2,376 persons on the Fort Yuma Indian Reservation. Main article: Quechan language. The Quechan language is part of the Yuman language family. Main article: Fort Yuma Indian Reservation. The Fort Yuma Indian Reservation is a part of the Quechan’s traditional lands. Established in 1884, the reservation, at 32°47’N 114°39’W, has a land area of 178.197 km2 (68.802 sq mi) in southeastern Imperial County, California, and western Yuma County, Arizona, near the city of Yuma, Arizona. Both the county and city are named for the tribe. Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Classification of indigenous peoples of the Americas. Native Americans in the United States. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay, Russian Federation.

- Region of Origin: US

- Framing: Unframed

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Size Type/Largest Dimension: Medium (Up to 10\

- Date of Creation: 1930-1939

- Color: Black & White

- Original/Reprint: Original Print

- Type: Photograph