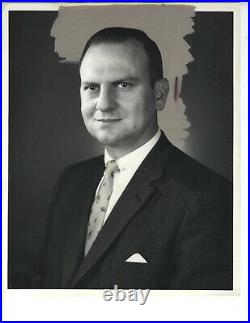

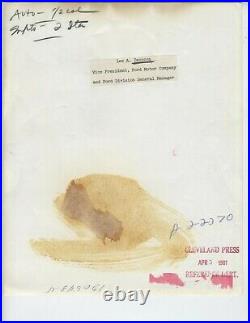

A VINTAGE ORIGINAL 8X10 INCH PHTOO FROM 1961 DEPICTING LEE A. IACOCCA VICE PRESIDENT, FORD MOTOR COMPANY AND FORD DIVISION GENERAL MANAGER. Lido Anthony “Lee” Iacocca was an American automobile executive best known for the development of Ford Mustang and Pinto cars, while at the Ford Motor Company in the 1960s, and for reviving the Chrysler Corporation as its CEO during the 1980s. Iacocca, the visionary automaker who ran the Ford Motor Company and then the Chrysler Corporation and came to personify Detroit as the dream factory of America’s postwar love affair with the automobile, died on Tuesday at his home in Bel Air, Calif. He had complications from Parkinson’s disease, a family spokeswoman said. In an industry that had produced legends, from giants like Henry Ford and Walter Chrysler to the birth of the assembly line and freedoms of the road that led to suburbia and the middle class, Mr. Iacocca, the son of an immigrant hot-dog vendor, made history as the only executive in modern times to preside over the operations of two of the Big Three automakers. In the 1970s and’80s, with Detroit still dominating the nation’s automobile market, his name evoked images of executive suites, infighting, power plays and the grit and savvy to sell American cars. He was so widely admired that there was serious talk of his running for president of the United States in 1988. Detractors branded him a Machiavellian huckster who clawed his way to pinnacles of power in 32 years at Ford, building flashy cars like the Mustang, making the covers of Time and Newsweek and becoming the company president at 46, only to be spectacularly fired in 1978 by the founder’s grandson, Henry Ford II. But admirers called him a bold, imaginative leader who landed on his feet after his dismissal and, in a 14-year second act that secured his worldwide reputation, took over the floundering Chrysler Corporation and restored it to health in what experts called one of the most brilliant turnarounds in business history. Iacocca with a Ford Mustang in the 1970s. The LIFE Images Collection, via Getty Images. Iacocca challenged the public. I want you to compare. Fusing his identity with his company’s to sell cars and win over Washington, Lee Iacocca was a celebrity C. For the modern era. As the 1980s unfolded, his commercials hammered at a theme: The pride is back. And so it seemed. The guaranteed loans were repaid in four years, seven years early. Its stock price soared, as did Mr. His achievement in restoring Chrysler was all the more impressive because it had begun in a national recession and matured against intense competition from America’s larger automakers, Ford and General Motors, and from a rising tide of imported cars from Japan and other countries. With tens of millions of copies in print, it still regales readers with its intimate look at the auto industry of Mr. Iacocca’s day, its cast of larger-than-life characters, its accounts of the author’s dismissal at Ford and his rescue of Chrysler. A Racist Attack on Children Was Taped in 1975. America’s Enduring Caste System. Continue reading the main story. Television commercials and news photographs had made him one of the nation’s best-known faces, an oval of grandfatherly features: a balding pate, a fleshy nose, mischievous eyes behind half-rim glasses, thin lips chomping an imported cigar, and a bland political smile that gave away nothing. A heroic figure to many Americans, he became chairman of a project to restore the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, and was in demand for speeches and public appearances that took on the color of a campaign. He conferred with President Ronald Reagan, members of Congress, governors and business leaders. He was mobbed by admirers and pursued by the press. Polls confirmed that a run for the White House was realistic, and his denials of political ambition only fueled public interest in a possible candidacy. Levin, a former reporter and Detroit bureau chief for The New York Times, wrote in “Behind the Wheel at Chrysler” (1995). At the peak of his popularity, many Americans believed not only that Iacocca held the answers to the nation’s economic ills but also that he should lead the country as president. But by the late 1980s, storm clouds that Mr. Iacocca and other auto executives had long ignored were gathering. The stock market had plunged in 1987, and Japan, long since recovered from the disasters of World War II, had become a world-class economic power, whose fuel-efficient cars were flooding the United States. Americans wanted reliable, well-built cars with innovations like airbags, and Honda and Toyota were supplying them. Iacocca, as he acknowledged, had drifted too far from day-to-day operations. By the 1990s, many American cars could not compete with Japanese innovations. The Iacocca magic, like Chrysler’s earnings, faded as the nation dipped into recession. He persuaded Congress to give some protection to the American auto industry from imported cars, but Japan just set up factories to build cars in the United States. Iacocca, then 37, in 1961 beside a new model of the Ford Fairlane. The year before he became general manager of the Ford Division of the Ford Motor Company. Iacocca barnstormed the country, demonizing the Japanese as alien invaders. He argued that Chrysler made better cars, that Japan’s “Teflon kimono” had deceived Americans and that the United States was suffering from a national inferiority complex. Trying to reverse the decline, Mr. Iacocca established partnerships with Mitsubishi, Maserati and Fiat, but they were no panacea. Finally surrendering to pressures to step down, he hired Robert J. Eaton, the head of G. S European operations, as his designated successor, and retired as Chrysler’s chairman and chief executive in 1992. “He’s like Babe Ruth, ” Bennett E. Bidwell, a retired Chrysler executive, said of Mr. He hit home runs and he struck out a lot. But he always filled the ballpark. He was born Lido Anthony Iacocca on Oct. 15, 1924, in Allentown, Pa. One of two children of Nicola and Antoinette Perrotto Iacocca, immigrants from San Marco, Italy, who named him after the Venice beach resort. He and his sister, Delma, grew up in Allentown. Their father had little education. He lost nearly everything but his Orpheum Weiner House in the Depression. But he later acquired several movie theaters and opened one of the country’s first car-rental companies with a small fleet of Fords, and Lido grew up talking cars with his father. Iacocca with his wife, Mary, in 1974. John Olson/The LIFE Images Collection, via Getty Images. “The Depression turned me into a materialist, ” Mr. Iacocca recalled in his autobiography. Years later, when I graduated from college, my attitude was:’Don’t bother me with philosophy. I want to make ten thousand a year by the time I’m 25, and then I want to be a millionaire. He also heard anti-Italian slurs in streets and schoolyards. While attending Allentown High School, he suffered a severe case of rheumatic fever. Unable to compete in sports, he pushed himself in his studies and graduated with honors in 1942. Lingering effects of the illness kept him out of World War II. At Lehigh University in nearby Bethlehem, Pa. He became a talented debater, had excellent grades and in 1945 graduated after three years with a bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering. He also impressed a Ford recruiter and was hired for an executive training program. Instead of engineering, he saw his future in marketing in the postwar boom years and lined up a job in sales in Ford’s Chester, Pa. Office, assisting dealers in the eastern Pennsylvania region. He decided to change his foreign-sounding first name to Lee, a serious concession for a young man proud of his ethnicity. He worked endless hours in the 1940s and early’50s, honing his speaking skills, studying sales trends and coordinating the strategies of his dealers. Iacocca married Mary McCleary, a Ford receptionist in Chester. They had two children, Kathryn Iacocca Hentz and Lia Iacocca Assad, who survive him, as do his sister, Delma Kelechava, and eight grandchildren. His first wife died in 1983 from complications of diabetes. In 1986 he married Peggy Johnson, a former flight attendant. The marriage was annulled in 1987. In 1991 he married Darrien Earle, whom he divorced in 1994. Iacocca preparing to film a TV commercial at an assembly plant in 1983. He became one of the nation’s best-known faces, an oval of grandfatherly features. Ted Thai/The LIFE Images Collection, via Getty Images. It took a decade for Mr. Iacocca to distinguish himself in Ford’s huge work force. Then he had a clever idea for a sales pitch. The idea was so successful regionally that Ford turned it into a national campaign and made him the corporate director of truck marketing. He also came to the attention of Robert S. McNamara, Ford’s vice president for car and truck sales and a future Ford president and secretary of defense. As a McNamara protégé, he learned to be an executive – to run meetings, analyze trends and mediate the often competing interests of Ford’s bean-counting financial analysts and its aggressive marketing and sales forces. He also learned the subtle, sometimes brutal, strategies of the executive scramble – to court allies, evaluate and undercut rivals, whatever it took to gain the next rung up the corporate ladder. Associates said he could humble a subordinate for a mistake one day and praise him the next. He once fired an executive and, on the way to the door, reminded him of their families’ dinner date later in the week. McNamara as vice president and general manager of the Ford Division in 1960, and four years later secured his place in automotive history by bringing out the Mustang, a small, rakish car with bucket seats and a floor shift that appealed to affluent young buyers and motorists of all ages who had dreamed of owning a sports car. Its success landed Mr. Iacocca and the Mustang on the covers of Time and Newsweek in the same week in April 1964. Iacocca became a favorite of reporters, who delighted in his candor, rare in the car industry. He produced other winners – the Maverick to compete with imports, the Lincoln Continental Mark III to challenge G. There were missteps: The Pinto burst into flames in rear-end collisions, and lives were lost. For years he opposed airbags, mandatory seatbelts and other safety items, insisting they did not sell cars. Iacocca with Frank Sinatra, left, and Barbara Sinatra in 1988, when he worked for Chrysler. He had reveled in the glitzy perquisites of his lofty position at Ford, traveling in a private Boeing 727 and entertaining in lavish suites. Ron Galella/WireImage, via Getty Images. But he outmaneuvered rivals for the executive suite and was named president of Ford in 1970, the No. 2 post, reporting only to the chairman, Henry Ford II. In the next eight years, as gasoline prices and foreign competition rose, Mr. Iacocca cut costs, streamlined operations and turned unprofitable divisions around. He nurtured managers who challenged conventional wisdom and solicited ideas from dealers and unions. He also began to revel in the glitzy perquisites of his lofty position. He traveled in a private Boeing 727, entertained in lavish Ford suites at the Waldorf Astoria in New York and Claridge’s in London, and partied with Frank Sinatra and other celebrities. His extravagances reportedly offended Mr. Iacocca’s relationship with the boss had never been close. Ford visited his office only a few times in his eight years as president. Their families rarely socialized. The company was publicly held, but Mr. Ford remained autocratic, deciding the fates of executives who came and went. Iacocca in July 1978, saying he just did not like him. He never gave more detailed reasons. Some industry observers said Mr. Ford could not tolerate a nonfamily rival, especially one of Mr. In his memoir, Mr. Iacocca detailed a long struggle between them, and called Mr. Ford a man of limited vision with ethnic and racial biases. Several months later, Mr. It was debt-ridden, losing millions and had virtually no credit. It was not enough. He turned to the government for help, igniting a national debate over a bailout. Iacocca at his home in Bel Air, Calif. After retiring as Chrysler’s chairman and chief executive in 1992, he invested in electric bicycles, olive oil and other ventures. Emilio Flores for The New York Times. Iacocca did not ask for a handout, or even a loan, just a federal guarantee of loans from banks and other creditors. Taking him at his word – that he could resurrect Chrysler, that it was too important to be allowed to fail – Congress passed and President Jimmy Carter signed the loan guarantee, enabling the company to get back on its feet. In 1987, Chrysler acquired American Motors and its Jeep division. Its Jeep Grand Cherokee was introduced in 1992, the year Mr. Iacocca retired, and became one of the biggest sellers in Chrysler history. Iacocca moved to Bel Air, Calif. Where he invested in electric bicycles, olive oil and other ventures and promoted diabetes research. But he was restless for action. Chrysler rebuffed it and canceled plans to name its headquarters and technology center in Auburn Hills, Mich. Iacocca, whose action was portrayed as a betrayal of the company he had rescued. In 1998, Daimler-Benz A. Iacocca said it might not have happened if his takeover had succeeded. The company is now owned by the Italian company Fiat. In addition to his autobiography, Mr. Iacocca wrote “Talking Straight” (1988) with N. Kleinfield, then a reporter for The Times, and Where Have All the Leaders Gone? (2007) with Catherine Whitney. In 2008, months before Chrysler and General Motors declared bankruptcy after years of mounting losses, Mr. Iacocca visited Auburn Hills and was greeted with thunderous applause by a thousand Chrysler workers. “Don’t get panicked, ” he told them. Things are going to be O. Now is the time to show your stuff. We don’t have any alibis. The truth is automobiles in America are still a vital business. American auto executive Lee Iacocca became a national celebrity for steering the Chrysler Corporation away from bankruptcy toward record profits in the 1980s. Who Was Lee Iacocca? Lee Iacocca joined the Ford Motor Company in 1946. He rose rapidly, becoming president of Ford in 1970. Though Henry Ford II fired Iacocca in 1978, he was soon hired by the nearly bankrupt Chrysler Corporation. Within a few years Chrysler was showing record profits, and Iacocca was a national celebrity. Lido Anthony Iacocca, generally known as Lee Iacocca, was born to Italian immigrants Nicola and Antonietta in Allentown, Pennsylvania, on October 15, 1924. Iacocca suffered a serious bout of rheumatic fever as a child, and as a result he was found medically unfit for military service in World War II. During the war, he attended Lehigh University as an undergraduate. He then received a master’s degree in engineering from Princeton University. I was raised to give back. I was born to immigrant parents and was fortunate to become successful at an early age. Climbing the Ranks at Ford and the Mustang. Iacocca’s engineering degree landed him a job at the Ford Motor Company in 1946. He soon left engineering for sales, where he excelled, then worked in product development. Iacocca also moved up the ranks at Ford, becoming a vice president and general manager of the Ford division by 1960. One of Iacocca’s accomplishments was helping to bring the iconic Mustang – an affordable, stylish sports car – to the market in 1964. In 1970, Iacocca became Ford’s president. However, the straight-talking Iacocca clashed with Henry Ford II, scion of the Ford family and chairman of the auto company. The tense relationship between the two led to Ford firing Iacocca in 1978. A few months after leaving Ford, Iacocca was hired to head the Chrysler Corporation, which was then in such financial distress that it was in danger of bankruptcy. This gave Iacocca the breathing room he needed to revamp and streamline operations. During Iacocca’s tenure, the popular minivan was added to the Chrysler vehicle lineup. The company edged into profitability in 1981 and repaid its government loans in 1983, years ahead of schedule. The True Story Behind’Ford v Ferrari. BY COLIN BERTRAM NOV 13, 2019. Iacocca’s success in turning Chrysler around made him a national celebrity. President Ronald Reagan asked him to help coordinate fundraising efforts for the restoration of Ellis Island and the Statue of Liberty. Two books written by Iacocca, his 1984 autobiography Iacocca and Talking Straight (1988), became best-sellers. He even made an appearance on the popular 1980s TV show Miami Vice. Iacocca retired from Chrysler in 1992. He was then able to devote more time to the Iacocca Family Foundation, a charity that supports diabetes research (Iacocca’s first wife, Mary, suffered from diabetes and died from complications related to the disease). Philanthropy is now a big part of my life, with the Iacocca Foundation funding cutting-edge research to find a cure for diabetes. Iacocca also worked with Kirk Kerkorian on an attempted hostile takeover of Chrysler in the mid-1990s. Despite the thwarted takeover attempt, Iacocca resumed his role as a Chrysler pitchman in 2005, appearing in ads with Jason Alexander and Snoop Dogg. Iacocca’s compensation for the commercials was sent to his foundation. He remained a booster for the U. Car industry, though his frustration with both public and private leadership was the subject of his third book, Where Have All the Leaders Gone? After losing his first wife in 1983, Iacocca married Peggy Johnson from 1986 to 1987. He had another short-lived marriage to Darrien Earle from 1991 to 1994. In his later years, he enjoyed spending time with his two daughters, Kathryn and Lia, from his first marriage and his grandchildren. Iacocca died on July 2, 2019, in Bel Air, California. Lido Anthony “Lee” Iacocca /? October 15, 1924 – July 2, 2019 was an American automobile executive best known for the development of Ford Mustang and Pinto cars, while at the Ford Motor Company in the 1960s, and for reviving the Chrysler Corporation as its CEO during the 1980s. [1] He was president and CEO of Chrysler from 1978 and chairman from 1979, until his retirement at the end of 1992. He was one of the few executives to preside over the operations of two of the Big Three automakers. Iacocca authored or co-authored several books, including Iacocca: An Autobiography (with William Novak), and Where Have All the Leaders Gone? Portfolio Magazine named Iacocca the 18th-greatest American CEO of all time. 1995 “Return” to Chrysler. Chrysler’s 2009 bankruptcy. Other work and activities. Later life and death. Iacocca was born in Allentown, Pennsylvania, to Nicola Iacocca and Antonietta Perrotta, Italian Americans (from San Marco dei Cavoti, Benevento) who had settled in Pennsylvania’s steel-production belt. Members of his family operated a restaurant, Yocco’s Hot Dogs. [4] He was said to have been christened with the unusual name “Lido” because he was conceived during his parents’ honeymoon in the Lido district in Venice. However, he denied this rumor in his autobiography, saying that is romantic but not true; his father went to Lido long before his marriage and was traveling with his future wife’s brother. Iacocca graduated with honors from Allentown High School in 1942, and Lehigh University in neighboring Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, with a degree in industrial engineering. [2] He was a member of Tau Beta Pi, the engineering honor society, and an alumnus of Theta Chi fraternity. After graduating from Lehigh, he won the Wallace Memorial Fellowship and went to Princeton University, where he took his electives in politics and plastics. He then began a career at the Ford Motor Company as an engineer. Iacocca was instrumental in the introduction of the Ford Mustang. Pictured here is a 1965 Mustang convertible. Iacocca joined Ford Motor Company in August 1946. After a brief stint in engineering, he asked to be moved to sales and marketing, where his career flourished. [6] His campaign went national, and Iacocca was called to the Dearborn headquarters, where he quickly moved up through the ranks. On November 10, 1960 Iacocca was named vice-president and general manager of the Ford Division; in January 1965 Ford’s vice-president, car and truck group; in 1967, executive vice-president; and president on December 10, 1970. Iacocca participated in the design of several successful Ford automobiles, most notably the Ford Mustang, the Continental Mark III, the Ford Escort and the revival of the Mercury brand in the late 1960s, including the introduction of the Mercury Cougar and Mercury Marquis. He promoted other ideas which did not reach the marketplace as Ford products. These included cars ultimately introduced by Chrysler – the K car and the minivan. Iacocca also convinced company boss Henry Ford II to return to racing, claiming several wins at the Indianapolis 500, NASCAR and the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Eventually, he became the president of the Ford Motor Company, but he clashed with Henry Ford II. Main article: Ford Pinto. The Pinto entered production beginning with the 1971 model year. Iacocca was described as the “moving force” behind the Ford Pinto. [11] This was largely due to recalls of its Dodge Aspen and Plymouth Volare, both of which Iacocca later said should never have been built. [dubious – discuss] Iacocca joined Chrysler and began rebuilding the entire company from the ground up and bringing in many former associates from Ford. Also from Ford, Iacocca brought to Chrysler the “Mini-Max” project, which, in 1983, bore fruit in the highly successful Dodge Caravan and Plymouth Voyager. Hal Sperlich, the driving force behind the Mini-Max at Ford, had been fired a few months before Iacocca. He had been hired by Chrysler, where the two would make automotive history together. Iacocca arrived shortly after Chrysler’s introduction of the subcompact Dodge Omni and Plymouth Horizon. The Omni was a derivative of Chrysler Europe’s Chrysler Horizon, one of the first deliberately designed “World Cars”, which resulted in the American and European cars looking nearly identical externally. However, underneath remarkably similar-looking sheetmetal, engines, transmissions, suspensions, bumpers and interior design were quite different. Cars even used VW-based engines (while the European models used Simca engines), as American Chrysler did not have an engine of an appropriate size for the Omni until the 2.2L engine from the Chrysler K-Car became available. Ironically, some later year base model U. Omnis used a French Peugeot-based 1.6L engine. The Dodge Aries, a typical K-Car. Realizing that the company would go out of business if it did not receive a large infusion of cash, Iacocca approached the United States Congress in 1979 and successfully requested a loan guarantee. In order to obtain the guarantee, Chrysler was required to reduce costs and abandon some longstanding projects, such as the turbine engine, which had been ready for consumer production in 1979 after nearly 20 years of development. Chrysler released the first of the K-Car line, the Dodge Aries and Plymouth Reliant, in 1981. Similar to the later minivan, these compact automobiles were based on design proposals that Ford had rejected during Iacocca’s (and Sperlich’s) tenure. In addition, Iacocca re-introduced the big Imperial as the company’s flagship. The new model had all of the newest technologies of the time, including fully electronic fuel injection and all-digital dashboard. Chrysler introduced the minivan, chiefly Sperlich’s “baby”, in late 1983. It led the automobile industry in sales for 25 years. [12] Because of the K-cars and minivans, along with the reforms Iacocca implemented, the company turned around quickly and was able to repay the government-backed loans seven years earlier than expected. The Jeep Grand Cherokee design was the driving force behind Chrysler’s buyout of AMC. Iacocca desperately wanted it. Iacocca led Chrysler’s acquisition of AMC in 1987, which brought the profitable Jeep division under the corporate umbrella. It created the short-lived Eagle division. By this time, AMC had already finished most of the work on the Jeep Grand Cherokee, which Iacocca wanted. The Grand Cherokee would not be released until 1992 for the 1993 model year, the same year that Iacocca retired. Throughout the 1980s, Iacocca appeared in a series of commercials for the company’s vehicles, employing the ad campaign, “The pride is back, ” to denote the turnaround of the corporation. Iacocca retired as president, CEO and chairman of Chrysler at the end of 1992. In 1995, Iacocca assisted in billionaire Kirk Kerkorian’s hostile takeover of Chrysler, which was ultimately unsuccessful. The next year, Kerkorian and Chrysler made a five-year agreement which included a gag order preventing Iacocca from speaking publicly about Chrysler. In an April 2009 Newsweek interview, Iacocca reflected on his time spent at Chrysler and the company’s current situation. This is a sad day for me. It pains me to see my old company, which has meant so much to America, on the ropes. But Chrysler has been in trouble before, and we got through it, and I believe they can do it again. If they’re smart, they’ll bring together a consortium of workers, plant managers and dealers to come up with real solutions. These are the folks on the front lines, and they’re the key to survival. Let’s face it, if your car breaks down, you’re not going to take it to the White House to get fixed. But, if your company breaks down, you’ve got to go to the experts on the ground, not the bureaucrats. Every day I talk to dealers and managers, who are passionate and full of ideas. No one wants Chrysler to survive more than they do. So I’d say to the Obama administration, don’t leave them out. Put their passion and ideas to work. Because of the Chrysler bankruptcy, Iacocca lost part of his pension from a supplemental executive retirement plan, and a guaranteed company car during his lifetime. The losses occurred after the bankruptcy court approved the sale of Chrysler to Chrysler Group LLC, with ownership of the new company by the United Auto Workers, the Italian carmaker Fiat and the governments of the United States and Canada. Presentation by Iacocca on Where Have All the Leaders Gone? April 23, 2007, C-SPAN. In 1984, Iacocca co-authored (with William Novak) an autobiography, titled Iacocca: An Autobiography. [2] The book used heavy discounting which would become a trend among publishers in the 1980s. [16] Iacocca donated the proceeds of the book’s sales to type 1 diabetes research. In 1988, Iacocca co-authored (with Sonny Kleinfeld) Talking Straight, [17] a book meant as a counterbalance to Akio Morita’s Made in Japan, a non-fiction book praising Japan’s post-war hard-working culture. Talking Straight praised the innovation and creativity of Americans. On April 17, 2007, Simon & Schuster published Iacocca’s book, Where Have All the Leaders Gone? Co-written with Catherine Whitney. [19][20] In the book, Iacocca writes. Where the hell is our outrage? We should be screaming bloody murder. But instead of getting mad, everyone sits around and nods their heads when the politicians say, Stay the course. You’ve got to be kidding. This is America, not the damned Titanic. I’ll give you a sound bite: Throw the bums out! Iacocca partnered with producer Pierre Cossette to bring a production of The Will Rogers Follies to Branson, Missouri, in 1994. He also invested in Branson Hills, a 1,400-acre housing development. In 1993, he had joined the board of MGM Grand, led by his friend Kirk Kerkorian. [22] He started a merchant bank to fund ventures in the gaming industry, which he called “the fastest-growing business in the world”. Iacocca founded Olivio Premium Products in 1993. Olivio’s signature product was an olive oil-based margarine product. Iacocca appeared in commercials for Olivio. Iacocca joined the board of restaurant chain Koo Koo Roo in 1995. [26] In 1998, he stepped up to serve as acting chairman of the troubled company, and led it through a merger with Family Restaurants (owner of Chi-Chi’s and El Torito). He sat on the board of the merged company until stepping down in 1999. In 1999, Iacocca became the head of EV Global Motors, a company formed to develop and market electric bikes with a top speed of 15 mph and a range of 20 miles between recharging at wall outlets. In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan appointed Iacocca to head the Statue of Liberty-Ellis Island Foundation, which was created to raise funds for the restoration of the Statue of Liberty and the renovation of Ellis Island. [29] Iacocca continued to serve on the board of the foundation until his death. Following the death of Iacocca’s wife Mary from type 1 diabetes, he became an active supporter of research for the disease. He was one of the main patrons of the research of Denise Faustman at Massachusetts General Hospital. In 2000, Iacocca founded Olivio Premium Products, which manufactures the Olivio line of food products made from olive oil. He donated all profits from the company to type 1 diabetes research. In 2004, Iacocca launched Join Lee Now, [30] a national grassroots campaign, to bring Faustman’s research to human clinical trials in 2006. Iacocca was an advocate of “Nourish the Children”, an initiative of Nu Skin Enterprises, [31] since its inception in 2002; he even served as its chairman. He helped donate a generator for the Malawi VitaMeal plant. Iacocca led the fundraising campaign to enable Lehigh University to adapt and use vacant buildings formerly owned by Bethlehem Steel, including Iacocca Hall on the Mountaintop Campus of Lehigh University. Today these structures house the College of Education, the biology and chemical engineering departments, and The Iacocca Institute, which is focused on global competitiveness. Iacocca played Park Commissioner Lido in “Sons and Lovers”, the 44th episode of Miami Vice, which premiered on May 9, 1986. The name of the character is his birth name, which was not used in the public sphere due to the trouble of mispronunciation or misspelling. Iacocca was married to Mary McCleary on September 29, 1956. They had two daughters. Mary Iacocca died from type 1 diabetes on May 15, 1983. Before her death, Iacocca became a strong advocate for better medical treatment of type 1 diabetes patients, who frequently faced debilitating and fatal complications, and he continued this work after her death. Iacocca’s second marriage was to Peggy Johnson. They married on April 17, 1986, but in 1987, after nineteen months, Iacocca had the marriage annulled. He married for the third time in 1991 to Darrien Earle. They were divorced three years later. Iacocca resided in Bel Air, Los Angeles, California, during his later life. [32] He died on July 2, 2019, at his home in Bel Air, at the age of 94. [33] The cause was complications of Parkinson’s disease. [34][35] His funeral was held on July 10, 2019 at St. Hugo of the Hills Roman Catholic Church and he was buried at White Chapel Memorial Cemetery in Troy, Michigan. Iacocca meets with President Bill Clinton on September 23, 1993. In his 2007 book Where Have All the Leaders Gone? Iacocca described how he considered running for president in 1988 and was in the planning stages of a campaign with the slogan “I Like I”, before ultimately being talked out of it by his friend Tip O’Neill. Polls at the time confirmed that he had a realistic chance of winning. Pennsylvania Governor Bob Casey discussed with Iacocca an appointment to the U. Senate in 1991 after the death of Senator John Heinz, but Iacocca declined. Politically, Iacocca supported the Republican candidate George W. Bush in the 2000 presidential election. In the 2004 presidential election, however, he endorsed Bush’s opponent, Democrat John Kerry. [38] In Michigan’s 2006 gubernatorial race, Iacocca appeared in televised political ads endorsing Republican candidate Dick DeVos, [39] who lost. Iacocca endorsed New Mexico Governor Bill Richardson for President in the 2008 presidential election. In 2012, he endorsed Mitt Romney for President. On December 3, 2007, Iacocca launched a website to encourage open dialogue about the challenges of contemporary society. He introduced topics such as health care costs, and the United States’ lag in developing alternative energy sources and hybrid vehicles. The site also promotes his book Where Have All the Leaders Gone. It provides an interactive means for users to rate presidential candidates by the qualities Iacocca believes they should possess: curiosity, creativity, communication, character, courage, conviction, charisma, competence and common sense. In 1985, Iacocca received the S. Roger Horchow Award for Greatest Public Service by a Private Citizen, an award given out annually by Jefferson Awards. The high amount of publicity that Iacocca received during his turnaround of Chrysler made him a celebrity and gave him a lasting impact in popular culture. In addition to his acting role in Miami Vice, Iacocca also made appearances on Good Morning America, Late Night With David Letterman and the 1985 Bob Hope TV special Bob Hope Buys NBC? [42] while concurrently it was common to see depictions of elderly, bespeckled businessmen with charismatic, salesman-like personas, such as in an ad campaign by the Rainier Brewing Company. [43] Iacocca’s image was also invoked by rival automaker Ford in the marketing campaign for the 1993 Mercury Villager minivan, which depicted a competing car company lead by an unhappy boss with a physical resemblance to Iacocca viewing the Villager with consternation because it is outselling their minivan. [44] Fictional businessmen and middle managers, such as Michael Scott on The Office, have been shown reading Iacocca’s books and attempting to emulate his methods. In a manner similar to Ronald Reagan, period pieces produced in subsequent decades have used images of Iacocca and the Chrysler K-car to invoke the 1980s. The 2009 film Watchmen, which is set in an alternative history 1985, took this in a unique direction by showing Iacocca being assassinated by the film’s antagonists, which has been said to have angered Iacocca when he learned about it. Iacocca, portrayed by Jon Bernthal, is a major character in the 2019 film Ford v Ferrari, which is a dramatization of the 1960s Ford GT40 program. The film was released shortly after Iacocca’s death. This item is in the category “Collectibles\Photographic Images\Photographs”. The seller is “memorabilia111″ and is located in this country: US. This item can be shipped to United States, Canada, United Kingdom, Denmark, Romania, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Estonia, Australia, Greece, Portugal, Cyprus, Slovenia, Japan, China, Sweden, Korea, South, Indonesia, Taiwan, South Africa, Thailand, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Ireland, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria, Bahamas, Israel, Mexico, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Switzerland, Norway, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Kuwait, Bahrain, Croatia, Republic of, Malaysia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, Trinidad and Tobago, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Antigua and Barbuda, Aruba, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Saint Kitts-Nevis, Saint Lucia, Montserrat, Turks and Caicos Islands, Barbados, Bangladesh, Bermuda, Brunei Darussalam, Bolivia, Ecuador, Egypt, French Guiana, Guernsey, Gibraltar, Guadeloupe, Iceland, Jersey, Jordan, Cambodia, Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, Sri Lanka, Luxembourg, Monaco, Macau, Martinique, Maldives, Nicaragua, Oman, Peru, Pakistan, Paraguay, Reunion, Vietnam, Uruguay, Russian Federation.

- Date of Creation: 1961

- Color: Black & White

- Original/Reprint: Original Print

- Antique: No

- Type: Photograph